[NOTE: Part I can be found here.]

Later on in his interview, the philosopher and bioethicist Julian Savulescu has much to say about what humans can do on the biological level to help make the world better, in the general sense as well as the biologic sense:

In my view, we should choose genes if those characteristics affect a person’s happiness. A rising percentage of kids today are on Ritalin for Attention Deficit Hyperactive Disorder. But that’s not because there’s suddenly been some epidemic of ADHD. It’s because you’re crippled as a human being if you have poor impulse control and can’t concentrate long enough, if you can’t defer small rewards now for larger rewards in the future. Having self-control is extremely important to strategic planning, and Ritalin enhances that characteristic in children at the low end of impulse control. Now, if you were able to test for poor impulse control in embryos, I believe we should select ones with a better chance of having more choices in life, whether you want to be a plumber, a taxi driver, a lawyer, or the president.

Does he hear himself? One of the dangers of “playing God” is to think we know what we do not know. I’m referring to the consequences of decisions such as what Savulescu is proposing here. Hubris is a mild word for what he’s displaying. People with ADHD are “crippled as human beings?” Yes, they have certain problems, but so does everyone—including, I imagine, Savulescu himself. In fact, for some people with ADHD, there might even be other characteristics going hand-in-hand with ADHD that are a plus. Some are creative, energetic, and out-of-the-box thinkers who’ve contributed much to society.

We are not equipped to measure the worth of a life, and the more we think we can, and the more circumstances we include in our deity-like measuring and eliminating, the further we have gone towards the territory of “life unworthy of life” Nazi-esque judgments.

In other words, Savulescu (along with his mentor, Singer) gives me the willies.

Here Savulescu addresses—or thinks he addresses—the problems inherent in eugenics and the Nazi comparison:

People concerned about eugenics remember the Nazi program of sterilization and the extermination of people deemed to be unfit. Now it’s important to recognize this wasn’t unique to Nazi Germany. The extermination part was, but sterilization was common through Europe and the United States. Many states in the U.S. had eugenics laws so people who were intellectually disabled or mentally ill were sterilized against their will. This kind of eugenics was one of the darker sides of the 20th century.

But eugenics just means having a child who is better in some way. Eugenics is alive and well today. When people screen their pregnancies for Down syndrome or intellectual disability, that’s eugenics. What was wrong with Nazi eugenics was that it was involuntary. People had no choice. People today can choose to utilize the fruits of science to make these selection decisions. Today, eugenics is about giving couples the choice of a better or worse life for themselves.

Yes, one of the many problems with Nazi eugenics was that it was involuntary. It was a huge problem, although in their own hubris the Nazis didn’t see it that way at all. But it was hardly the only problem. Another problem is that all eugenics, not just the coercive variety—as I’ve already indicated—comes complete with an alarming degree of hubris that ignores the unintended consequences of such policies, much as all large-scale central social planning does. But it’s a persistent leftist/statist delusion that the person currently doing the planning is smart enough to avoid (or ignore) those inherent problems.

Also, didn’t Savulescu already state the following (emphasis mine), in the same interview from which I’m taking all these quotes?:

Q: So you don’t see any fundamental ethical objection to human cloning?

A: In reality, hardly anybody does. Remember that 1 in 300 pregnancies involves clones. Identical twins are clones. They are much more genetically related than a clone using the nuclear transfer technique, where you take a skin cell from one individual and create a clone from it.

Q: But twins are not something we engineer. That just happened.

A: One of the big mistakes in ethics is to think that means make all the difference. The fact that we’ve done it or nature has done it is irrelevant to individuals and is largely irrelevant to society. What difference would it make if a couple of identical twins come not through a natural splitting of an embryo, but because some IVF doctor had divided the embryo at the third day after conception? Should we suddenly treat them differently? The fact that they arose through choice and not chance is morally irrelevant.

So, according to Savulescu’s own belief system, wouldn’t the distinction between voluntary eugenics and coerced eugenics be one of means, and therefore wouldn’t it be a “big mistake” to think it’s a difference that makes a difference? I assume that he would answer that question by saying that it’s more than a distinction of means; that somehow distinctions based on voluntariness or coercion are of a very different order. But why would that be, if we are bioengineering a Brave New World?

Come to think of it, Savulescu reminds me quite forcibly of the character Mustapha Mond in Huxley’s masterpiece:

Resident World Controller of Western Europe, “His Fordship” Mustapha Mond presides over one of the ten zones of the World State, the global government set up after the cataclysmic Nine Years’ War and great Economic Collapse. Sophisticated and good-natured, Mond is an urbane and hyperintelligent advocate of the World State and its ethos of “Community, Identity, Stability”. Among the novel’s characters, he is uniquely aware of the precise nature of the society he oversees and what it has given up to accomplish its gains. Mond argues that art, literature, and scientific freedom must be sacrificed to secure the ultimate utilitarian goal of maximising societal happiness. He defends the genetic caste system, behavioural conditioning, and the lack of personal freedom in the World State: these, he says, are a price worth paying for achieving social stability, the highest social virtue because it leads to lasting happiness.

I would also assume (although I’m really not sure) that Savulescu would say that he differs from Mond in that he doesn’t believe in caste systems, and he doesn’t want to sacrifice personal freedom either. Well if so, bully for him. But such a smart person should be smart enough to see that once the sort of things he’s advocating become normal in society, the rest can easily follow, and that once social engineers are in charge personal freedom will always suffer greatly.

Savulescu does seem to have an inkling of some problems, although even there his insights seem interspersed with mistaken assumptions:

I think we are the biggest threat to ourselves. The elephant in the room is the human being.

This seems to be true. But then he says this:

For the first time in human history we really are the masters of our destiny. We’ve got enormous potential to have unprecedentedly good lives. We’ll be able to live twice as long. With our computers and the Internet, we already are smarter than any of our predecessors.

I don’t agree with any of the assertions in the above quote. I don’t see us as the “masters of our destiny”, and since Sevulascu has already just said that the elephant in the room is the human being, I doubt he actually thinks so either. Is that not a contradiction, right there?

And then there’s the phrase “unprecedentedly good lives.” “Good” measured how? People certainly don’t seem happier than they used to, if one measures “good” that way. But there are other ways to measure “good” than “comfortable” or “easy” or even “long” (see this).

And will we actually ever be able “to live twice as long” as the oldest of us do now? Perhaps, but perhaps not. It remains to be seen.

Lastly, does Savulescu really think that computers and the internet have made human beings “smarter than any of our predecessors”? I certainly don’t see that effect of computers. Whatever the reason, I see us as creeping closer towards the situation portrayed in the film “Idiocracy,” and although computers have made some people more well-informed, at least, they seem to have given others more access to false information and circles of hatred and paranoia.

Savulescu went on to add:

But we also have the possibility to completely shackle ourselves, if not destroy ourselves. The Internet is a good example. In George Orwell’s 1984, Big Brother was placing us under surveillance, controlling and censoring everything that happened. In some ways we already are under surveillance. But my worry is not the government—at least not in the U.K. or the U.S.; it’s each other. As soon as we publish something, it’s immediately pumped around the Internet to every fanatical group, which then mobilizes within minutes and creates such momentum that it doesn’t matter what you said or what the truth is; what matters is the perception. So we now live under a kind of censorship of each other and that’s just going to increase.

He said that right after he said “With our computers and the Internet, we already are smarter than any of our predecessors.” Seems contradictory to me.

I will close with something I wrote earlier in one of my posts about Peter Singer (the teacher Savulescu credits as his mentor):

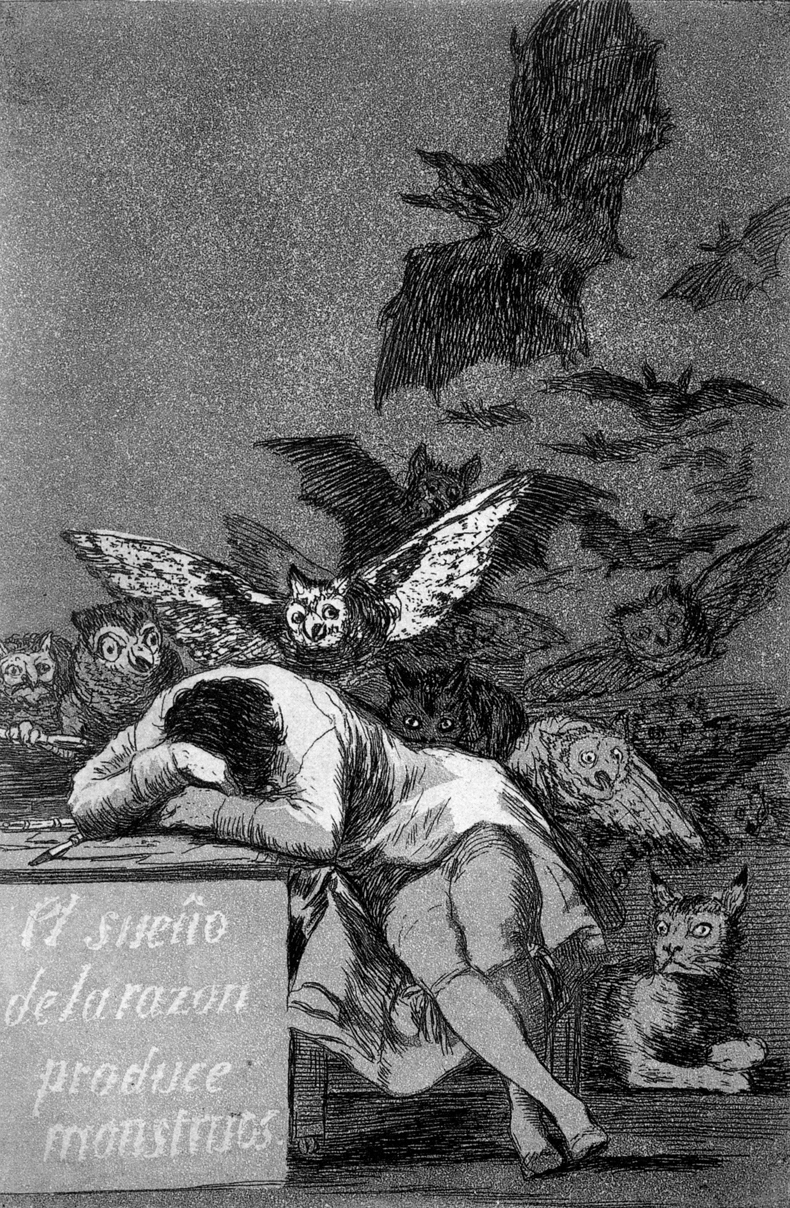

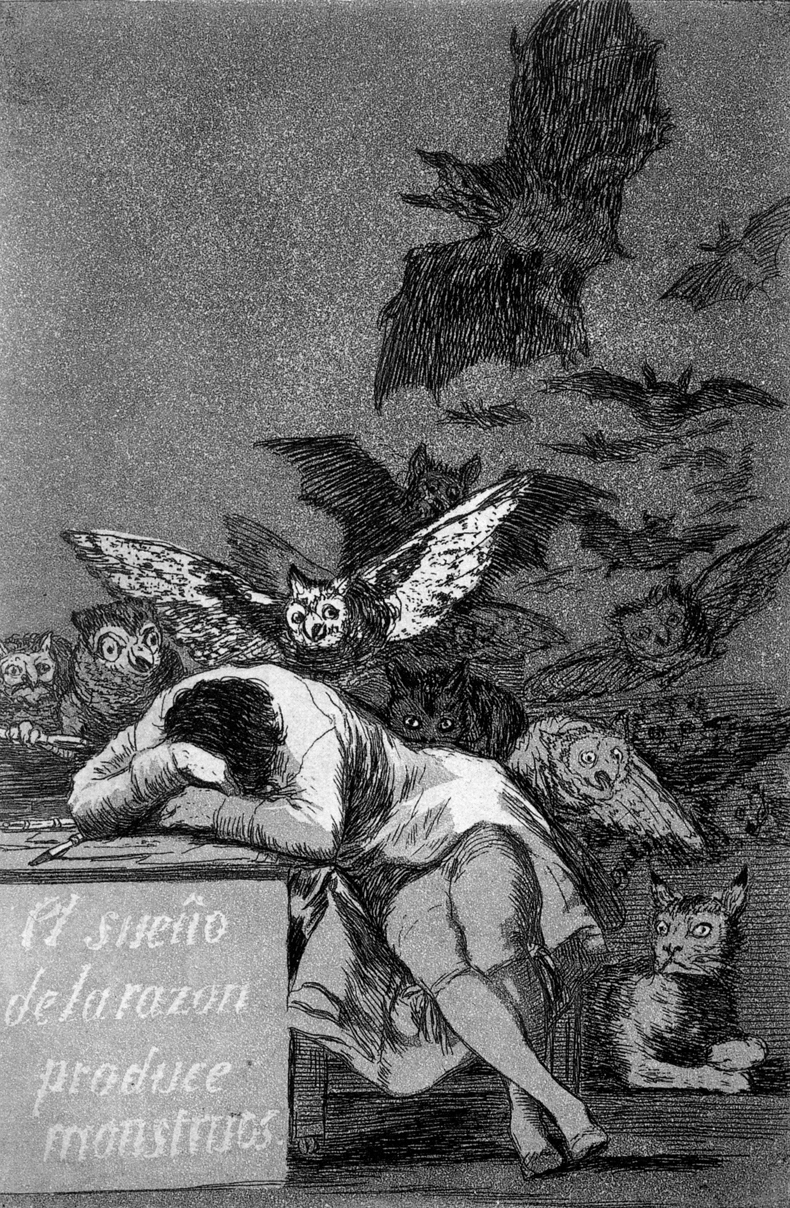

When I was a child of about twelve years old, I came across (I think it was in an encyclopedia) a Goya etching entitled “The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters.” Here it is:

At the time, I was puzzled by the title. Did it mean that when reason goes to sleep, bad things happen? Or did it mean that when reason gets free reign, bad things happen? Since then, I’d always seen it interpreted the first way; after all, Goya himself wrote “Imagination abandoned by reason produces impossible monsters.” But that’s not the full quote, which adds, “united with her, she is the mother of the arts and the source of her wonders.”

I’d add to “imagination” something like “emotion,” or perhaps “the eternal and ancient human truths.”

Here’s more:

“Kearney (2003) suggests two different meanings based on the dream/sleep debate. Firstly, ‘reason must govern the imagination’, it must be watchful, otherwise the ”’forces of darkness’, will be ‘˜unleashed on humanity’. Alternatively, a more romantic approach is that the ‘˜rationalist dreams’ promoted by the ‘˜Enlightenment’ are just as capable of producing their own ‘˜monstrous aberrations’.”

Reading about Peter Singer immediately made me think of that Goya etching.

[NOTE: The interview with Savulescu was first written up in 2015, but it’s been recently republished.]