I keep reading online discussions in which people assume that there’s been a big increase in teen killings, both murder and suicide. It’s taken almost as a given, but I rarely if ever see anyone citing statistics to back up the assertions.

So of course I tried to look it up. First question: has there been a rise in teen suicide? Answer: no and yes (the following quotes are from an article dated November 2017):

An increase in suicide rates among US teens occurred at the same time social media use surged and a new analysis suggests there may be a link.

Suicide rates for teens rose between 2010 and 2015 after they had declined for nearly two decades, according to data from the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Why the rates went up isn’t known.

The study doesn’t answer the question, but it suggests that one factor could be rising social media use.

What I get out of that is that for two decades suicide rates had been declining among teens, and there’s a recent uptick. Not only can the recent uptick not be explained, but I would guess that the previous two-decade decline cannot be explained, either. But I doubt most of you were aware of that decline; I wasn’t.

If you think that the strength of marriage and family has decreased over those decades, it certainly doesn’t seem to have been reflected in an increase in the suicide rates among teens. And as for the recent uptick, does it even begin to compare with the high figures from the 90s?

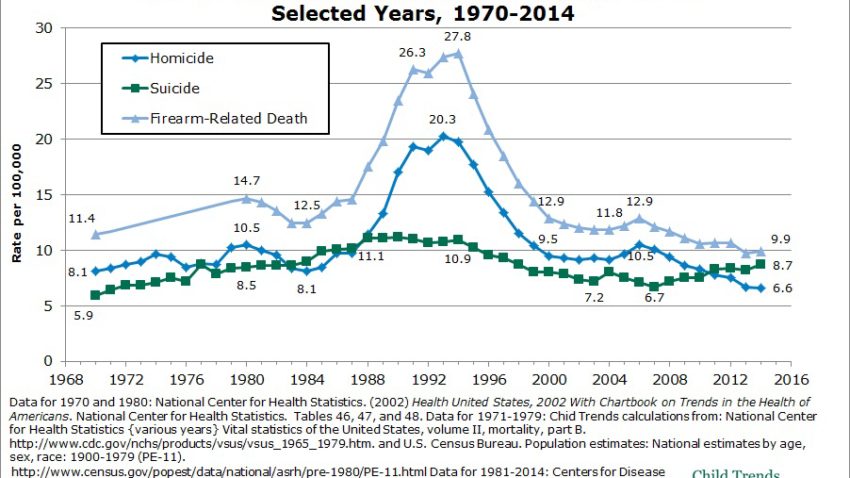

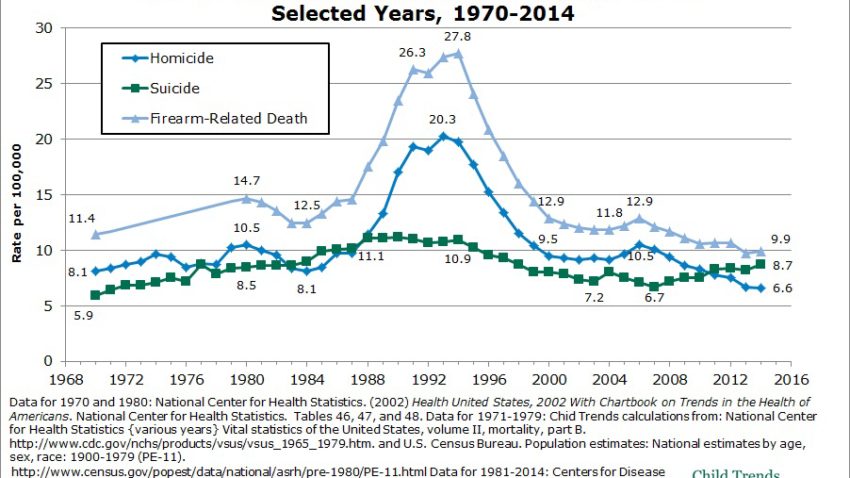

An organization called Child Trends tracks those statistics, and here’s a chart that shows suicides and homicides by teens aged 15-19 (as well as teen victims of homicides) from the 1970s to 2014, which should include most of the years involved in that uptick:

It’s a pretty shocking chart. What was going on with homicides and gun deaths from 1988 to 2000? I’m sure you can generate theories—and social scientists certainly have—but no one knows. One leading theory is, of course, that the widespread use of antidepressants was a highly contributing factor, but research does not indicate that was the case.

As for the line on the chart for suicides, the suicide bulge for those years was much much smaller and more gradual, with a gradual decline and then another slight upward climb that hasn’t reached the previous levels. Note that the chart only applies to teens between 15 and 19 years of age, although I am fairly sure that those are the peak teen years for those behaviors.

But it matters which age groups we’re talking about, because it turns out that between the ages of 15-24 suicides actually declined during that same period roughly corresponding to the 90s:

Before 1990, youth suicide rates in the U.S. had increased over the course of several decades. The rates were said to have tripled between 1953 and 1957 and between 1983 and 1987, rising from 2.46 to 9.64 per 100,000 persons 15 to 24 years of age; however, the increase might not have been as great as was initially believed, owing to a possible undercounting of youth suicides.7 Starting in 1990, however, the suicide rate in the U.S. among youths and young adults between 10 and 24 years of age began declining steadily, falling from 9.48 to 6.78 per 100,000 persons between 1990 and 2003.8 Yet between 2003 and 2004, the suicide rate increased by 8%, to 7.32 per 100,000””the largest single-year increase since 1990.

So how can we even generalize about this?

What’s more, here’s what that author has to say about the effect of SSRI prescriptions on the phenomenon:

It may be no coincidence that the long decline in youth suicide rates in the U.S. began soon after the start of the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) era, which started in 1987 with the introduction of fluoxetine (Prozac, Lilly)…

In many countries, a correlation has been found between increases in prescriptions for newer antidepressants and decreased suicide rates. However, the experience has been the opposite in Iceland and Norway, where suicide rates have risen or have remained unchanged even as antidepressant prescribing increased substantially. None of these studies establish a causal relationship between antidepressant use and suicide rates, of course, and many other factors can affect suicide rates…But the preponderance of the ecological evidence points to a potential protective effect for antidepressants with respect to suicide.

Not long after SSRIs were introduced, however, an unsettling thought was raised: that instead of protecting patients, SSRIs might have resulted in a number of suicides…

In the U.S., concerns about antidepressants led the FDA in 2004 to require the addition of a boxed warning to the labeling of these medications. This warning mentioned an increased risk of suicidal thoughts and behaviors in association with the use of antidepressants in pediatric patients. More recently, the boxed warning was revised to include young adults up to 24 years of age.

Both versions of the warning discuss the need to carefully monitor patients who begin treatment with antidepressants; incidentally, such advice had been given to clinicians long before the advent of SSRIs. The current version also mentions that depression and other psychiatric disorders are themselves associated with an increased risk of suicide. Recently, however, concern has grown that instead of promoting the monitoring of patients who initiate antidepressants, these well-intentioned actions have had unintended consequences: underdiagnosis and under-treatment of depression in patients of all ages and increased suicide rates in young people, following years of steady decline in the suicide rate.

I’ll leave it there for now. Books could be written on the subject, and no doubt have. But I’m not going to be writing one this afternoon.

, which Frankl considered the deepest motivator in human life.