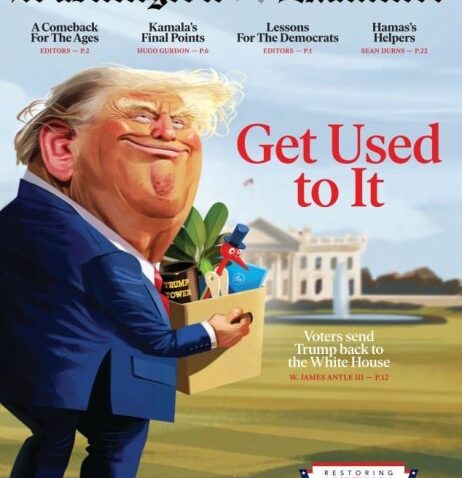

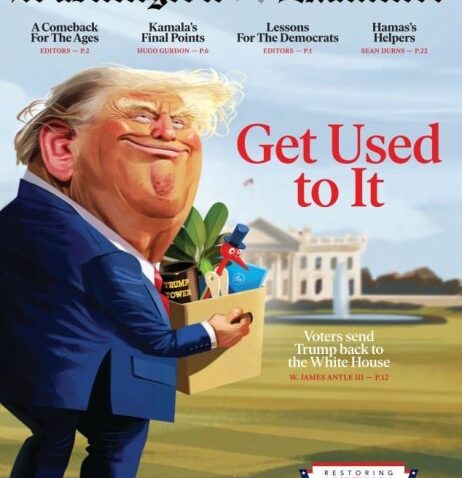

Love it. The artist got the facial expression just right, walking the thin line between a gloating smirk and a broad broad smile:

Love it. The artist got the facial expression just right, walking the thin line between a gloating smirk and a broad broad smile:

Turley is one of those lawyers I came to deeply respect years ago. He’s an Independent, as far as I can tell, but more importantly he’s a person who’s not afraid to follow the truth wherever it leads him. Sure, now and then I disagree with him; what else is new? But most of the time I think he’s spot on, as well as informative about the law.

And so I bring you this column of Turley’s written the day after the election:

Nearly two years ago, I wrote that Democratic prosecutors’ lawfare campaign against Donald Trump would make the 2024 election the single largest jury decision in history. Now that the verdict is in, the question is whether prosecutors will continue their unrelenting campaign against the president-elect and his companies.

The jury’s decision: acquittal

More [emphasis mine]:

The election reflected a certain gag sensation for a public fed a relentless diet of panic and identity politics for eight years. The 2024 election will come to be viewed as one of the biggest political and cultural shifts in our history. It was the mainstream-media-versus-new media election; the Rogan-versus-Oprah election; the establishment-versus-a-disassociated-electorate election.

It was also a thorough rejection of lawfare. One of the things most frustrating for Trump’s opponents was that every trial or hearing seemed to give Trump a boost in the polls. As cases piled up in Washington, New York, Florida and Georgia, the effort seemed to move more toward political acclamation than isolation.

Now, these cases are now legal versions of the Flying Dutchman — ships destined to sail endlessly but never make port.

If there is a single captain of that hapless crew, it is Special Counsel Jack Smith. For more than a year, Smith sought to secure a verdict in one of his two cases in Washington and Florida before the election. His urgency was seemingly shared by Judge Tanya Chutkan in Washington, but by few other judges or justices.

Around 2 am, Smith became a lame-duck prosecutor. Trump ran on ending his prosecutions and can cite a political mandate for it. Certainly, had he lost, the other side would be claiming a mandate for these prosecutions.

Trump’s new attorney general could remove Smith and order the termination of his continued prosecution. That is less of a problem in Florida, where a federal judge had already tossed out the prosecution of the classified documents case, which some of us saw as the greatest threat against Trump.

In Washington, Chutkan, who proved both motivated and active in pushing forward the election interference case, could complicate matters. Under federal rules, it is up to Chutkan to order any dismissal. …

In the end, Trump read the jury correctly. Once the lawfare was unleashed, he focused on putting his case to the public and walked away with a clear majority decision. It is unlikely that this will end all of his lawfare battles, but it may effectively end the war.

I don’t think these cases are going anywhere even if one or two sputters on, because there’s always appeal to SCOTUS and I don’t think the Court would let a guilty verdict stand.

Also there’s this, although I don’t know if anything will come of it:

Jack Smith:

Preserve your records. pic.twitter.com/Toazp1EATk

— House Judiciary GOP ?????? (@JudiciaryGOP) November 8, 2024

As President Obama once said, when he was riding high: “Elections have consequences.”

Or will they continue to lie to themselves that Trump’s win was due to sexism and racism, despite the fact that Trump increased his share of votes from all minority groups?

Although Democrats exhibit a few glimmerings here and there of actual understanding, I just don’t think it’s widespread. And besides, because Democrats have built their entire pitch for many years on identity politics and abortion and fear of the right, what alternative pitches do they have? If they faced the bankruptcy of their ideas, it would require an entire overhaul.

Then again, it’s sobering that Harris didn’t lose by sixty points, as she should have. She was that poor a candidate. However, the MSM probably accounted for much of her support, because the way they frame the news still matters to a significant number of people. There’s also habit – it’s hard to vote for a Republican when you’ve only voted for Democrats for your entire life. Take it from me. And Donald Trump is strong stuff for an entry-level vote.

No, not that kind of weightlifting.

This kind:

I can’t remember the last time I saw Caroline Glick smile, but there it is. Of course, she’s aware that the road ahead isn’t easy. But she’s allowing herself a few moments of celebration, and for those moments she looks as though a great weight has lifted from her shoulders.

I feel much the same way. Looking back, I never felt this way when Trump was elected in 2016, although I do recall feeling relief that Hillary Clinton would not be president. But I thought Trump was an untried, untested blowhard – which, come to think of it, he was. It only took a few months to start feeling better about his presidency, and somewhere about halfway through I really started enjoying it. But I was aware that it might end after the 2020 election, and when COVID and lockdowns occurred, I became fairly certain that Trump would not be re-elected.

Looking back, I see from this post of mine, written in March of 2020, that I correctly saw what a future Biden presidency would hold:

The near-certainty that the Democratic nominee will be Biden raises the specter of the Democrats coming back and picking up where Obama left off, only worse. We dodged that bullet in 2016. But the question has always been whether that was only a little blip on the long Gramscian march and the Democrats’ hope for permanent takeover of the American electorate. Simply put: will the US inexorably move further and further left?

Biden’s supposed “moderation” is only such compared to Bernie. And I doubt that a single one of my Democrat friends (who are quite typical, politically, of much of the Democratic electorate) would hesitate to vote for either Biden or Sanders or any other sentient (or semi-sentient) being if that person becomes the Democratic nominee. They hate Trump with a white hot passion.

Biden’s running mate will probably be a woman, someone like Klobuchar or Kamala Harris (remember her?). Someone female and young, preferably ethnic although Biden really doesn’t need that since he already has the black vote pretty well sewn up because of his Obama connection.

I believe Biden as president would be more a less a figurehead, and the people in charge would be the same people who were prominent in the Obama administration, doing the same things only more so because they feel the country is ready for more open leftism. The Deep State will really go to town, as well. Legislation, however, depends on who controls Congress. If it’s the Democrats, the sky’s the limit.

I have never for a moment understood why anyone would have seen Biden as a potential moderate, but perception of his supposed middle-of-the-road quality was one of the main reasons he became president. For the next four years, for the most part, blogging consisted of chronicling a series of bad decisions with bad results.

When Trump announced he was running again, I wasn’t happy. I knew that his support in the GOP primaries would be very strong and would be enough to eliminate other and younger contenders such as DeSantis. And Trump came with several steamer trunks of baggage, actually a long caravan. Simply put: I didn’t think he was likely to win the general.

Tuesday night proved me wrong, I’m happy to say. And now I get to enjoy a period in which, like Caroline Glick, I can do a little happy-dance. It’s not that I’m unaware of the enormity of the problems looming. And I certainly don’t think it will be smooth sailing or anything resembling it. But there is a sense of relief and some of the weight has lifted for now.

And quickly, we get to enjoy news like this:

Qatar has told the political leaders of the Hamas terror group that they were no longer welcome in the Gulf state, Israeli media reported on Friday.

According to the Hebrew-language Kan outlet, the decision was communicated to the Palestinian jihadists “in recent days.”

“Recent days” – how many? Let’s guess.

Another thing about a second Trump term is that he’s more seasoned. Yes, he is also facing the challenges of undoing the damage the Biden administration did. But he knows the ropes, as it were. And I like to think that his four years out of power, his legal struggles, and his survival on July 13, have deepened him in some way. This time around he’s got the help of smart guys such as Vivek and Elon, and the calm of Tulsi Gabbard – plus, well, I’m not 100% sure of RFK but I guess we’ll find out. I have no idea how long this very interesting coalition will last, or what fruit it will bear, but I do find it intensely unusual and potentially very good.

And what of the left? They’ve tried internal sabotage, lawfare, and catastrophizing. Two of their acolytes tried assasination. Now they are rending their garments. But I’m not sure their lies will be as effective this time. And I think they will lose control of the House.

And another bonus: I don’t see Kamala Harris making a political comeback in 2028. Or ever. Biden? He looked happy making his speech the other day, and sounded more coherent than he has in four years. Have a happy retirement, Joe, and keep wearing that MAGA hat. What Obama might be cooking up I really don’t know. But one thing I think we can safely say is that this will not be his fourth term as president.

I finally gave up on ascribing any meaning to the polls this election cycle. The only thing they seemed to be saying with any consistency was that the race was balanced on a razor’s edge, but that even that could be wrong and either candidate actually could win decisively.

Well, thanks a lot; that’s very helpful.

But before I gave up on polls altogether, I noticed that a pollster for Rasmussen named Mark Mitchell, who frequently put out videos on YouTube, was saying something very different, and he was consistent too. He was saying (1) Trump would win not only the Electoral College but the popular vote as well, and (2) the other pollsters who said it was close weren’t just mistaken, they were lying.

I watched him for several weeks and he kept saying the same thing. But I finally stopped watching because I had no way to know if he was correct or way off, and I didn’t want to give myself false hope.

Well, now he gets bragging rights, big time:

So although it’s true that most pollsters were wrong – Mark Mitchell says purposely so, in what amounted to a psyop designed to bring in more money to Harris from donors and to keep her voters from becoming apathetic – they weren’t all wrong.

And take a look at this graphic:

… but there will be a delay while I transport a friend back and forth from the hospital for a test.

Just thought I’d let you know.

Yes, the Amish:

The state’s famed “Pennsylvania Dutch” registered to vote in “unprecedented numbers” in response to a January federal raid on a local raw milk farm in Bird in Hand, Pa., a source familiar with the situation told The Post. …

The Amish community saw the move as an overzealous reach by the government and was planning to vote for GOP presidential candidate Donald Trump, whose party favors less government intervention.

“That was the impetus for them to say, ‘We need to participate,’ ” the source said of local Amish voters. “This is about neighbors helping neighbors.”

The Amish community rallied around Miller, who cited his religious beliefs as a reason for not adhering to Food and Drug Administration guidelines.

I would imagine there are a number of communities of a religious bent that don’t ordinarily vote in large percentages but who aren’t especially happy with what they see as government overreach.

This election has generated so much to think about that it could serve as subject matter for posts for years. And yes, books will be written about it – although not by me.

So I’ll just start tackling topic after topic, trying to pace myself, knowing that I’ll only be able scratch the surface of what has happened.

I’ve already read many articles on the post-election fights within the Democrat Party in which one group blames another. For example, there’s this one that describes the war of words between the head of the party in Philadelphia and the Harris campaign:

McPhillips added: “If there’s any immediate takeaway from Philadelphia’s turnout this cycle, it is that Chairman Brady’s decades-long practice of fleecing campaigns for money to make up for his own lack of fundraising ability or leadership is a worthless endeavor that no future campaign should ever be forced to entertain again.”

The criticism directed at Brady, the longtime head of the Democratic City Committee, came shortly after the former member of Congress told The Inquirer that he felt no responsibility for the red wave that descended on the state.

Brady said money was an issue, and criticized the Harris campaign for paying only about “half” of the money the city committee requested for its get-out-the-vote effort. Those funds, otherwise known as “street money,” are used to pay committee members to get out the vote.

Then there’s the Biden people versus Harris people versus Obama people issue. For a good example of a piece describing that brouhaha, please see this:

President Joe Biden is furious that he is being blamed for Kamala Harris’ failed campaign and is going to war against his detractors in a bid to reunite the Democratic Party behind his middle-class credentials.

Biden remains convinced that his longtime ties to the trade unions and working-class men would have swayed the 2024 presidential election vote in his favor. Right to the end of the campaign, he insisted he would have beaten Donald Trump. …

The president’s circle was enraged that the finger-pointing had already begun in the Harris campaign within hours of Trump’s resounding victory, with most of the barbs aimed directly at the Oval Office.

According to Politico’s ‘Playbook’, Biden loyalists were especially bitter over unnamed quotes in a Politico article claiming the president was the “singular reason” for the damning defeat and saying a Democratic primary race would have given Harris more time and opportunity to run a better campaign.

The Biden aides blamed Barack Obama’s advisers for the Harris missteps that ultimately cost her any hopes of the White House.

You get the idea. Success has many fathers but failure is an orphan.

Most of these articles assume that politics is a game that’s all about tactics and strategy. And I have little doubt that tactics and strategy are huge. But they’re not everything. And they can’t overcome a lousy product. I don’t think the Democrats have learned the lesson illustrated in this classic story, which is that maybe the dogs didn’t like it:

Once upon a time a pet food company created a new variety of dog food and rolled out a massive marketing campaign to introduce the product. Despite hiring a first-rate advertising agency, initial sales were very disappointing. The agency was fired and a new agency and a new campaign was launched. Sales continued to disappoint. If anything, they fell even further. In desperation, the CEO called in all of the top executives for a brainstorming session to analyze what had gone wrong with the two campaigns and how a new campaign might revive sales.

The meeting went on for hours. Sophisticated statistical analysis was brought to bear on the problem. One VP argued that the mix of TV and print ads had been messed up. Another argued that the previous campaigns had been too subtle and had failed to feature the product with sufficient prominence. Another argued that the TV ad campaign had focused too much on spots during sporting events and not enough on regular programming with a broader demographic. Another argued the opposite–not enough sports programming had been targeted. After the debate had raged for hours, the CEO felt they had accomplished very little. He asked if anyone else had any theories that might explain the failure of the new product. Finally, one newly hired employee raised his hand and was recognized. Maybe the dogs don’t like it, she said.

In recent years the Democrats have been serving the American people some dog food that tastes like – dare I use the word? – garbage. Of course, some dogs like garbage, but a lot of dogs want something tastier. To use another famous saying, this time one ascribed to Lincoln – you can fool all the people some of the time, and some of the people all the time, you cannot fool all the people all the time. If the deception is too egregious, you will have trouble fooling enough people to win an election.

The truth is that they managed to accomplish it in 2020 (or was there a large cheating factor? More about that in another post coming soon). They didn’t manage in 2024, in part because I think the public recognized that Biden hadn’t been as advertised. People have experienced the Biden administration and suffered from many aspects of it. Then there was the obvious deception later on, as Biden’s cognitive powers declined further and the pretense was maintained that he was fine. More trust was broken when there was a sudden admission by the party that Biden needed replacement, and then instead of asking the people what they might want, Harris was installed as substitute. Then there was the further pretense that she was “joyful” instead of strangely inauthentic and tremendously inarticulate. Plus plenty of other obvious lies such as the idea that inflation was caused by widespread price gouging rather than the Biden/Harris policies. And that Harris was supposed to simultaneously be of the administration and yet not of the administration. That was too much of a bogus Zennish koan for the public to swallow.

And on and on and on. No amount of “messaging” and “narrative” will change those things. But the Democrats seem to think they can say anything and people will believe it. Vance is “weird” says Walz, one of the weirdest candidates ever. Kamala is the gracious uniter, as she spews mendacious venom about Trump and Republicans. And on and on and on some more.

You can summarize the whole thing by saying that this election represents the triumph – for the moment, anyway – of reality over imagology. “Imagology” is a word used by Czech author Milan Kundera in his book Immortality, in the following passage :

…[C]ommunists used to believe that in the course of capitalist development the proletariat would gradually grow poorer and poorer, but when it finally became clear that all over Europe workers were driving to work in their own cars, [the communists] felt like shouting that reality was deceiving them. Reality was stronger than ideology. And it is in this sense that imagology surpassed it: imagology is stranger than reality, which has anyway long ceased to be what it was for my grandmother, who lived in a Moravian village and still knew everything through her own experience: how bread is baked, how a house is built, how a pig is slaughtered and the meat smoked, what quilts are made of, what the priest and the schoolteacher think about the world; she met the whole village every day and knew how many murders were committed in the country over the last ten years; she had, so to speak, personal control over reality, and nobody could fool her by maintaining that Moravian agriculture was thriving when people at home had nothing to eat. My Paris neighbor spends his time an an office, where he sits for eight hours facing an office colleague, then he sits in his car and drives home, turns on the TV, and when the announcer informs him that in the latest public opinion poll the majority of Frenchmen voted their country the safest in Europe (I recently read such a report), he is overjoyed and opens a bottle of champagne without ever learning that three thefts and two murders were committed on his street that very day.

…[S]ince for contemporary man reality is a continent visited less and less often and, besides, justifiably disliked, the findings of polls have become a kind of higher reality, or to put it differently: they have become the truth. Public opinion polls are a parliament in permanent session, whose function it is to create truth, the most democratic truth that has ever existed. Because it will never be at variance with the parliament of truth, the power of imagologues will always live in truth, and although I know that everything human is mortal, I cannot imagine anything that would break its power.

:

I think it’s a brilliant description, but I think that often reality, if obvious enough, can break the power of the imagologues, and that we’ve just seen a demonstration of that. And now we’re seeing the imagologues blame each other for not using imagology effectively enough, when in fact (to mix the metaphors) maybe the dogs just didn’t like it.

I’m still pinching myself about the election results. But it doesn’t seem like this will feature a repeat of the post-election reversals of 2020; the win was apparently too big for that. And yet still too close for comfort, given the abysmal candidacy of Kamala Harris.

I hope that Harris leaves the stage of national politics after she leaves the VP office. She doesn’t have much aptitude for it and I doubt the Democrats will be nominating her again.

Last night I didn’t look at any election results till after 9 PM. Too nervous. Once I started looking, it was clear that the signs were encouraging. So although it took me hours and hours to relax, I started feeling somewhat better by about 11 PM. I certainly hadn’t expected it to happen that soon.

There’s so much to think about. Strangely enough, I believe that an opinion column in non other than the NY Times summed up the general truth – at least, the following part:

“Populist Revolt Against Elite’s Vision of the US”

The assumption that Mr. Trump represented an anomaly who would at last be consigned to the ash heap of history was washed away on Tuesday night by a red current that swept through battleground states — and swept away the understanding of America long nurtured by its ruling elite of both parties.

No longer can the political establishment write off Mr. Trump as a temporary break from the long march of progress, a fluke who somehow sneaked into the White House in a quirky, one-off Electoral College win eight years ago. With his comeback victory to reclaim the presidency, Mr. Trump has now established himself as a transformational force reshaping the United States in his own image.

Because it’s the Times, of course, the article goes on to say that resistance to a female president was a factor. Should I add “goes on to say without evidence“? Because it was this candidate, not her being a female, that did her in, and this platform devoid of solutions or appeal to most people.

The rest of the article demonstrates the same stupidity – Trump violated standards (as though the left didn’t do that to a far greater extent in its attempt to destroy him), and is a “convicted criminal” (as though he isn’t the victim of kangaroo court persecution at the hands of the left and really is a criminal). There’s more outright lying in the piece, the repeat of Democrat talking points like the “dictator on day one” distortion and the like.

But I’m not going to dwell on the right now. Right now I want to enjoy the day. Hope you do, too.

So many things of interest! It’s a happy day.

(1) Konstantin Kisin understands. If you’re not familiar with his podcast Triggernometry, you should take a look sometimes.

(2) Harris has called Trump to concede. Yay!:

Harris discussed the importance of a peaceful transfer of power and being a president for all Americans, according to a senior Harris aide. Harris was expected to address supporters later Wednesday afternoon.

(3) Biden also called Trump. I bet Biden was secretly a bit happy, unlike Harris.

(4) Jack Smith will be throwing in the towel on his anti-Trump cases, at least for now. What a destructive charade he put on. Obviously, the goal was to hurt Trump’s changes of re-election. Ironically, he may have helped. In addition, Trump probably could have pardoned himself for the two federal cases in which Smith is prosecutor. What of the more local cases? What of Judge Merchan, for example?:

Should Merchan proceed with the sentencing as scheduled, he’ll face the unprecedented task of deciding whether to impose a prison sentence of up to four years on a defendant who is set to occupy the White House come January. If he does order Trump to prison, Trump almost certainly won’t be required to serve that sentence until after he leaves office in 2029.

Left out is the fact that the case was almost certainly doomed anyway in appeals court, because it was another complete travesty.

(5) This is well worth watching:

(6) It looks like the GOP will keep the House, although the margin will remain small. However, it’s still very very important to maintain control for a host of reasons. Then there’s also the question of who will replace McConnell in the Senate. Pleasant prospects to contemplate.