The Flight 1549 survivors escape to tell the tale

Disasters leaving no survivors are not only tragic and terrifying, they remain mysterious. If no one escapes to tell the tale, we are left to imagine how the unfortunate victims spent their last moments. Was the end quick, or did it involve terrible suffering? Was it chaotic and fear-filled, or cooperative and spiritual?

We are curious because we want to know more about human behavior under extreme conditions. We wonder how we would do in similar circumstances, although we sincerely hope we will never have to face them.

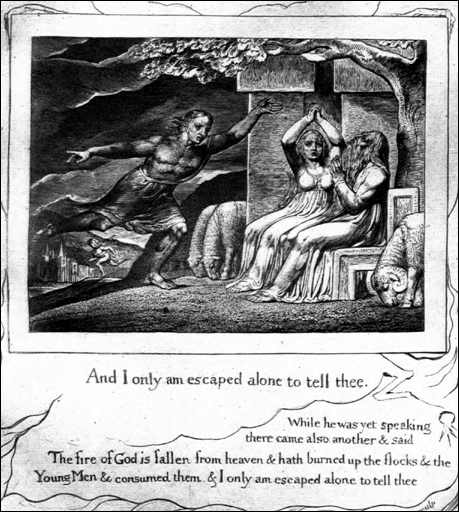

And so still another fascination of the Flight 1549 story is that, unlike the misfortunes of Job, or those of Ishmael in Moby Dick…:

…all escaped together to tell the tale.

And what a tale it is! One cannot help but be impressed not only by the mere logistics of their survival as well as its improbability, but by the near-unanimity of the passengers’ stories of calm and mutual assistance.

For a typical example, here’s a portion of the transcript of a Bill O’Reilly interview with survivor Fred Beretta:

REILLY: Now, at this point was the plane still quiet as you were descending down or were people getting a little scared?

BERETTA: It was still really quiet. I think everyone was just stunned. Sort of the reality of it was ”” people were just assimilating that.

O’REILLY: Do you remember what you were thinking?

BERETTA: I thought ”” I looked out the window and I thought there’s a good chance we’re going to die. And I did think about my family and started praying.

O’REILLY: Are you a religious man?

BERETTA: I am. Try to be.

O’REILLY: Were other people praying aloud?

BERETTA: I didn’t hear any, but I could tell. I just kind of glanced around, and people were either just sort of closing their eyes or, you know, sitting quietly for the most part. People were pretty calm.

Beretta describes an eerily quiet scene, much the opposite of the picture Hollywood usually conveys in the typical disaster movie. The Flight 1549 passengers had gone in an instant from a normal traveling day to an encounter with the high probability of their imminent mortality and, according to Beretta (and he should know), they were adjusting as best they could to the astonishingly rapid turn of events, quietly trying making their peace with whatever power they each believed in.

The Flight 1549 survivors’ stories are remarkably similar, leading to an assumption that they are highly reliable accounts of what actually occurred. Not only do most of these people mention the relative calm as the plane was going down (only a couple of sporadic emotional outbursts were reported on the part of a lone passenger or two), but passengers’ behavior after the touchdown was likewise serene and collected.

Of course, once the plane had “landed,” a sense of relief and a diminishing panic might be expected from the passengers. But the reality (and the passengers were no doubt aware of this) was that their situation at that time was only somewhat less perilous than in the moments before the splashdown. Drowning was a very real possibility, as well as death by hypothermia in the icy waters.

Rapid evacuation was therefore of the utmost importance, and a clawing for position, or even a stampede, would not have been surprising. But no such behavior occurred:

“We’re sitting with our heads down,” [survivor Carlos] described. “I’m there buckled in tight, and you just hear them over and over and over and you’re just praying.”

Carlos said the plane skidded to a stop on the river and he made it out onto a wing with the nearly freezing water rising around him and his fellow passengers.

“It was like one big family on that wing, everyone’s holding each other, this guy’s got that guy and this lady’s got that guy and no one wants to fall off,” Carlos said. “It was amazing, the human spirit, when it comes down to that everyone just got together, and was able to overcome and stay together, and everyone made it.”

And there’s this report from another passenger, a young Australian woman:

“There were no screams, tears, just a strange peace,…

It was a passenger who opened the exit door as “orderly chaos” ensued.

“There were a few women hyperventilating but I was really surprised at how calm everyone was. Normally I’d be the one in tears but honestly it happened too quickly. It was just survival instinct,” she said.

What accounts for the calm and the cooperation? Part of the cause may have been the rapidity of the entire event. From bird strike to touchdown was only three and a half minutes, and some people may have still been making the adjustment from normalcy to crisis and back again with hardly enough time to assimilate what was happening. Passenger Carl Bazarian probably speaks for many passengers (and perhaps even the crew) when he indicates he is still engaged in adjusting:

As Bazarian arrived at Jacksonville International Airport Friday morning, he told Channel 4 he was still “in a surreal world.”…

That sense of unreality will probably last quite a while. Although Bazarian and the others were spared the scenes of agony, mayhem, and death that often haunt survivors of disasters in which others have died or been seriously injured, that doesn’t mean that they were not traumatized and will need some time to readjust. But the lessons they (and we) have learned are profoundly positive ones about the possibilities for human behavior in times of great stress. I’ll leave the last word on the matter to Mr. Bazarian:

Bazarian said going through the experience bonded him with several other passengers.

“We’ll be close forever. It’s unbelievable. Keeping each other warm, assisting each other,” Bazarian said. “Great, great people. I mean really bonding. It’s incredible.”

Pingback:Instapundit » Blog Archive » THOUGHTS ON THE lack of panic on Flight 1549. Plus, cheerleading saves lives….

I haven’t been in a plane crash, ever – but I have been in a couple of earthquakes in crowded places – and the curious thing that I noticed was that people didn’t much panic and begin screaming, like in various disaster movies. In real life, people rather got very quiet and still, and quite calm. This was rather reassuring to me to know this … but very odd that it escaped the people who make movies.

I suppose it also helps that Robert Hays wasn’t flying the plane…

I am reminded, quirkily, of how this courage contrasts with a belief of my famously pessimistic father: Our family had experienced a true tragedy. A nurse, trying to say something – anything – which might help us feel better, said: “Well, difficult circumstances bring out the best in people.” Not missing a beat, my father authoritatively informed her “Also brings out the worst in people.”

Don’t know, but I really want to hear the tapes from the cockpit recorder.

Your insights are most valuable, and one of the evils of postmodernism and moral relatavism is that any nobility of the human spirit is generally ignored or derided. I am not a blogger or regular commenter, but read many blogs and news websites, including yours. As a fellow “apostate liberal”, to use Roger Simon’s phrase, I want you to know that your words are particularly appreciated. Please keep it up.

I have nothing but admiration for the the passengers and crew, but I hope they will be offered monitoring for PTSS.

Thank heaven they all got out. The occasion would be very different if their composure had reduced fatalities instead of eliminating them.

I just finished reading “Deep Survival” by Laurence Gonzales, thanks to Instapundits recomendation. It goes into detail about the psychological effects of being involved in a disaster and fighting for your life. The narrative structure is poor, but the content is stunning. A good read for NN.

I was driving in my car near NYC when all this happened, and I noticed the contrast between one of the radio reporters on WINS AM and the passengers who were just starting to be interviewed.

The reporter was almost hyperventilating, and he kept referring to the “panicked” passengers, despite simultaneously describing an orderly evacuation. I started to get the feeling that either he had no idea what the word “panicked” meant, or he was just speaking for himself!

I think that your observation about time might be the important part. They literally didn’t have TIME to be scared–they didn’t even have enough time to really process what was going on. If the engines had gone out at 35,000 feet and it took twenty minutes for the plane to go down, then there might have been a different situation.

I’ve been involved in two small plane “incidents”. One was a wheels up landing on grass. The other involved the loss of all electrical systems (although the engine kept running). Both occurred in the darkness of evening.

Interstingly, both events were serenely calm. There were four occupants on board the plane each time. And it was very quiet without hysterics or emotion.

From those incidents, I’ve come to realize that many events are not like those of the movies, but rather a calmer event.

By the way, I’m not a pilot. Just happened to be in the wrong place at the wrong time, on two different occasions. I fly in small planes a lot less.

Maybe they were all stunned — and grateful — by the fact that they had survived a crash landing and were all still alive.

DD – The gist of your post is indeed correct – that given twenty minutes to think about their situation more panic would have been expected. However, had the engines failed at 30,000 feet the aircraft could have glided to the airport of its choosing within its glideslope ability. Picking a nit, I know – but that’s just how I roll.

Perhaps a better example would be the Japan Airlines (I think) 747 that had a catastrophic decompression through its rear cargo door some years back. The explosion severed the hydraulic lines that controlled the elevator and rudder. On that particular flight the pilots struggled for control of the aircraft for about 45 minutes until finally impacting a mountain peak, killing all aboard. The passengers had time to write messages to loved ones which they tucked into their clothing. Incredibly moving story. The cockpit voice recorder transcripts are available somewhere online, I’m sure. They make for intense reading.

I often think with gratitude of Fordham University’s radio station, WFUV, and their calm, soothing broadcasts on 9/11. It absolutely helped to keep panic at bay. I was at work in the NYC metro area, away from TV. All the internet news sites were jammed, as well as my email. I was able to stream WFUV, though, to catch the news. The broadcasters stressed the importance of staying calm & collected. They played music with an American theme. Woody Guthrie singing “This Land Is Your Land” never sounded so beautiful as it did that day.

Pingback:If you were First Lady… | The Anchoress

The movie angle reminded me of the boundaries that were broken with the surreal silence of space in 2001 Space Oddysey. Less is very often more.

Take a look at how quick they were all out on that wing (40 seconds from splashdown) – Bird hit to Huck Finn trip down the river was less than 5 minutes.

The real point is that people don’t just automatically panic. They in the main stay calm and help one another. Now, all bets are off if there is no opportunity to help in a coordinated and caring manner. A sudden conflagration in a crowded theater comes to mind.

Perhaps their creator granted them the peace they were asking for.

I was a passenger in a station wagon that was clipped by another car trying to pass. There were about ten of us in the car, all college students on the way to a cave exploring adventure (we never got there). As the car fishtailed off the road going backwards at 65 MPH I remember having a detached feeling, as if I were watching the experience happening to someone else. I was in a rear facing jump seat next to the back of the vehicle. If we had rolled over or struck a tree or another car i am sure I would have been ejected and killed. I thought to myself that perhaps I should brace my feet against the ceiling in the event that the car might roll. A few seconds later the car stopped on the opposite side of the highway, still facing backward but upright. None of us were even scratched. Perhaps at the age of 18 I had an exaggerated sense of my own immortality, although I surely knew the laws of physics were immutable. Even now, 40 years later, my lack of fear astounds me.

So what is that has changed in us in 40 plus years? I cite this from a UPI story of the crash of a 727 at Salt Lake in Nov. 1965: ” “Everybody rushed for the doors before the plane stopped,” declared Air Force Lt. …”Then panic started.”

“One young fellow, a recent college graduate, tried to keep everyone calm, but he couldn’t do it. I don’t know if he survived.” The young officer from Malden, Mass., … was bitter. He kept saying no one had “consideration for other people, no consideration whatsoever.” ” This was a landing that was a “CFIT” “Controlled Flight Into Terrain”. The pilot came in too fast and short of the runway so there was no warning to the passengers. So what is it that makes us seem to be better in similar circumstances?

Calm appears to be a common reaction in the face of death. A famous scene from “In Darkest Africa” describes a lion attack in which either Stanley or Livingston–I can recall which–is overcome with euphoria as he’s being tossed around in the jaws of a lion. Fortunately, he was saved to write about it.

Unclebryan:

I happened to look up JAL 123 yesterday. It is still the worst single-plane disaster in history, with 520 deaths. But, incredibly, there were four survivors.

There may have been more, but rescuers assumed that all onboard must have been killed on impact and didn’t arrive at the crash site until the following morning.

9/11 made a lot of people think long and hard about what to do in an airliner emergency. Every time I step on a plane I instinctively go through a mental checklist of things that could go wrong and what I should do about them.

This reminds me of a car accident I was in over 10 years ago. Not nearly as serious, but my husband and I were on the freeway and a car cut us off, we swerved, sideswiped another car, then spun and flipped. By the grace of God, we were mostly fine, a few bumps and bruises. It could have been awful, but within seconds we knew everything was okay. The odd thing was that for several weeks afterwards I would suddenly burst into tears for no reason at all. I knew it had something to do with the accident. I wouldn’t be surprised to learn that the passengers on this flight will have similar, but more profound reactions. I would be fascinated to hear interviews a year from now.

The general makeup and respect for civility of the people going through the disaster has to have a lot to do with it.

I’d say the same group who trampled the walmart employee on black Friday would’ve been lucky to see a 50% survival rate in the event of such a splashdown.

I’m thinking of the Challenger shuttle mission…

Time had nothing to do with it. The people in the Twin Towers had plenty of time to panic, to trample each other as they left the building. They did not do so. The only places where panic takes hold are Hollywood, news rooms, and New Orleans.

When faced with grave danger, people crave authority. That was provided by the pilot and cabin crew, who gave authoritative commands on what to do. That calmed the passengers. It’s when passengers are left in the dark to fend for themselves that they panic.

I’m impressed that the evacuating passengers seemed to not make the classic mistake of grabbing their carry-on luggage to take with them, slowing the evacuation down. The urge to save their carry-ons has killed many a passenger in a crash. Perhaps the cold water pouring in the aircraft convinced them they needed to leave immediately without their laptops and overnight bags.

“Beretta describes an eerily quiet scene, much the opposite of the picture Hollywood usually conveys in the typical disaster movie.”

I remember some British disaster and monster films from the 60’s showing much more calm and measured response than you would see in similar Hollywood efforts, and always wondered if this was because many of the British directors had lived through the bombing of London in WW2, and had firsthand memories of how people really react under such conditions.

–

I read somewhere that a passenger announced “women and children first!” as the evacuation began. By reaffirming the moral order, that has a calming effect on the evacuation. People who ordinarily acknowledge this order, but who might otherwise be driven into a free-for-all by panic, will be snapped out of it and shamed into the behavior they know to be right.

On Thursday, I was reading The Unthinkable, about surviving disasters, when I saw the news about the flight. (The irony was not lost on me.) The author says that passivity, even paralysis, is the most common reaction to disasters. The book was fascinating, and I highly recommend it for those who are interested in these phenomena: http://www.amazon.com/Unthinkable-Survives-When-Disaster-Strikes/dp/0307352897/ref=pd_bbs_sr_1?ie=UTF8&s=books&qid=1232480094&sr=8-1

If you think this was a natural reaction, imagine this scene, but in the third world somewhere…

Yes, some will be resigned in the face of death, but particularly after a successful ditch, the evacuation could have been dreadful, but wasn’t and it’s a credit to the passengers, and especially the cabin crew and flight crew for setting the tone. Perhaps it also matters that it was a midweek flight, largely comprised of business people. Of course, there was the one guy who stripped and jumped in the water in panic…

“What accounts for the calm and the cooperation? Part of the cause may have been the rapidity of the entire event.”

It’s that they were a good group of people who didn’t feel entitled to push each other trying to get out the door. You have to wait your turn and if your unfortunate enough to be in a place that puts you at maximum distance from a door… well, that’s the roll of the dice / the way the cookie crumbles / your fate. Seems like people took it like that (mature adults) and it helped get them all out this time…

Unlike people trying to push their way into a concert or Wal-Mart sale…

I believe SteveH nailed it. Some people are civilized, and some are not.

Pingback:“Great,great people.” | PowerTowneDistro.com

Drowning was a very real possibility, as well as death by hypothermia in the icy waters.

Rapid evacuation was therefore of the utmost importance, and a clawing for position, or even a stampede, would not have been surprising.

How would fighting to reach the exit first save you from hypothermia?

Now it might have been different if the plane had obviously caught fire…

fighting to reach the exits (even with a fire) will likely slow your exit (because everyone else will be as well) unless you’re one of the first dozen, or so, people out. What civilized people learn, and hopefully execute, even under duress, is that controlling your instinctual urge can yield better results than responding to the animal impulses of your brain. But one has to learn that, whereas we’re all born with instinct- making it the default. It’s not about accepting your fate, it’s about making the best decision. It helps to also understand that if you doom yourself by being civilized, at least you’ve increased the odds of others surviving.

Isn’t it interesting that morality and civilization can bring you to a superior result in terms of survival of the species versus what nature and instinct would prescribe?

Just a comment about not having time to be scared. Those 3 1/2 minutes were terrifying.