The dance world and sexual harassment

Peter Martins has been accused of sexual harassment in his capacity as long-time director of the New York City Ballet and teacher at the company school. Martins has headed the company since the death of its founder George Balanchine in 1983—first as co-director with Jerome Robbins, and since 1990 as sole director.

That’s a long time to be in charge, and a lot of power. In fact, at this point Martins has directed the company for approximately the same amount of time as Balanchine did.

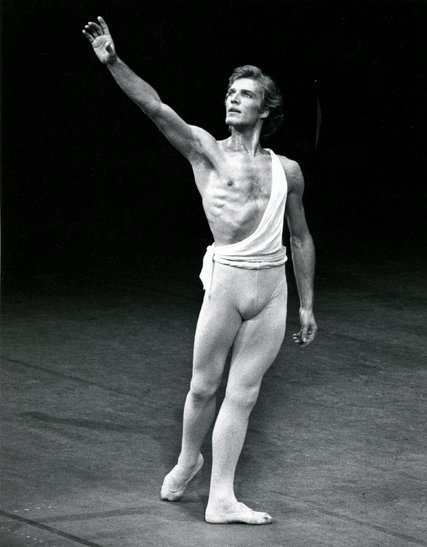

But Martins is no Balanchine (to be fair, nobody is). Balanchine was a master choreographer who changed the face of ballet and was extraordinarily prolific, and was also a strong and unique personality. Martins was primarily known as a dancer of cool classicism and chiseled strong-jawed blond good looks. Here he is in his dancing heyday, as he was when I saw him dance many times:

Martins has also choreographed quite a few dance works, and I’ve seen several of them—and detested every single one. They’re disjointed, boring, and difficult, and I’m hardly alone in saying that. For example, from an article in the NY Times in 2013:

Mr. Martins has long been castigated as a choreographer. All too many of his pieces are both heartless and sketchy.

On the other hand, I almost always enjoyed Martins’ dancing. There are basically two kinds of dancers, Dionysian and Apollonian, and Martins was an excellent example of the latter type.

But the scuttlebutt about him that I came across in the dance world (many years ago, I might add) was that he wasn’t a warm fuzzy guy, to put it kindly. That’s not an unusual phenomenon in ballet for directors and/or teachers, who tend (or tended; again, my information is rather out-of-date) towards the autocratic, although there were many exceptions. Ballet may look airy, but many of its stellar lights have been hard as nails. It used to be thought almost necessary; perhaps it still is.

Martins—like Balanchine and Barishnikov—was also heterosexual, which is hardly unknown in ballet but is certainly not a given. For Martins (as for Balanchine and Barishnikov), that meant that there were a number of romances and/or affairs and/or relationships with the female dancers around him. Martins has been married to star ballerina Darci Kistler since 1981 (after a shorter first marriage), and although they’ve had a few rough patches—including an allegation of physical abuse that was later withdrawn—they’ve remained together.

Their romance was a union of two people who were both already stars, however; Martins had little to nothing to do with her rise in the company, which had occurred during the Balanchine years. So it’s safe to say that Kistler became a star without much or even any help from Martins—in fact, I believe she was the last favorite of Balanchine (and he was so elderly and already starting to become ill), and she had such extraordinary physical prowess as a dancer that I think she probably did it on the strength of her dancing. Kistler herself has stated that she “didn’t have a deep personal relationship” with Balanchine, and I believe her. But she also said that Balanchine had taught her “how to live life” and that “all the things he said to me, echo.” Ballet directors (and even some ballet teachers) tend to have that total-immersion quality.

So, what about the harassment charges against Martin? It’s very unclear; all we know so far is that someone wrote an anonymous letter to the company stating nonspecific accusations of sexual harassment against him, and the company has taken the precaution of removing him from his teaching duties for the moment. If that description of what’s happened is correct, then of all the allegations of sexual offenses I’ve heard in the last couple of months, that just might be the most Kafkaesque.

But the story started me thinking about ballet and its relation to sexual harassment/abuse/assault. Ballet differs from other arts (and certainly from politics or broadcasting or even acting) in that the body is completely the instrument, the mechanism by which that art is expressed. There is nothing else, not even talk (as in acting). Not only that, but the way the body looks is nearly as important as the way it moves, or at least inextricably connected with it. It’s no exaggeration to say that virtually every dancer in the professional dance world is a physically beautiful person with an extraordinarily beautiful body. And even the older directors (such as, for example, Martins) have an aging version of the same, and often a personal magnetism and power that cannot be denied. It was part of the reason they were stars, although not all directors were once performers or stars.

But it all seems like a recipe for sex, doesn’t it?

The themes of ballet often involve love, as well—romantic, sexual, some combination of the two. So there’s no getting away from it.

What’s more, there’s often a lot of interaction and touching in the choreography and in the studio, even during class. Teachers touch their students all the time—that’s how they convey what’s needed—adjusting a hand, helping the dancer bend in the right direction by giving a little push, turning the head just so. Partners touch their partners all the time, and the communion between partners can be extraordinarily intimate. It can also lead to an actual romance (and of course sex) in real life—what little the dancers have of real life, that is, after the rigors of taking class and rehearsals and performances and shoe preparation and all the rest.

Company directors (the heterosexual ones, that is; I know less about the habits of the gay directors, but I’m assuming the story is not too different) often sleep with their dancers. They even sometimes marry them; Balanchine, for example, was famous for this, having married (and divorced) a whole series of them.

So the idea in ballet is not to eliminate the sex or the touching—I think that would be impossible—but to eliminate the harassment. How would “harassment” be defined in a world like that? Unwanted touching? Touching that goes beyond what’s required for the class or the choreography or the correction? Whether there is a quid pro quo for the sex: “sleep with me and I’ll make you a star”?

Even with all the sex that goes on there’s not usually an explicit quid pro quo in ballet—at least, that isn’t the way I’d always heard or read that it worked (no personal experience here, by the way). I believe what tends to happen more often is that the choreographer or director is attracted to the better dancers, the ones who already inspire him (or I suppose inspire “her”; for example, modern dance pioneer Martha Graham married one of her dancers, and “Men invaded her company – and her life – from time to time; but in her choreography they had a tendency to remain as sex objects, often scantily clad and explicitly animal”—but that’s a subject for another day). After all, if a director promotes a bad dancer, the problem will be revealed when she just can’t perform the choreography, because you can’t fake ballet technique.

And the dancer generally sleeps with the director because she’s genuinely intrigued by him, too—his power or his artistry or his looks or his grace or some combination of these qualities. There would ordinarily be no need for “harassment” of the usual sort; the sex happens as part of the big picture that draws these people together in the first place: their art and the spell it casts, and the realization that they can help further each others’ careers.

I’m pretty sure I’m not describing the way it works all the time. I would assume there are exceptions and scheming people who use sex to promise advancement or to get roles (or with the thought that they’ll get roles). It often doesn’t end well, either. But from what I recall hearing, the sex tends to come after the first big roles. And as far as Martins goes, I have no idea—zero—whether he sexually harassed anyone or not.

[NOTE: In the process of writing this post I watched some videos, and one of them features an interesting story told by a retired dancer about her coming-up years. Her mentor and director was Barishnikov, who plucked her out of the corps and promoted her. There seems to have been no sex of any sort involved in that process. The events she describes in this clip began when she was 18:

I’ve seen every single person she mentions in that video perform. Brings back good memories. At 22, Yaffe married—a conductor, not a dancer.]

Dancers are human, so course there are sexual games, good or ugly.

I know nothing at all about ballet but enjoyed reading your analysis very, very much.

Learned quite a lot about dance, dancers and human nature.

Brilliant post.

Someone who did music for a dance company and was sexually involved with one of the dancers was a good friend of mine for a few years. I confess I never liked dancers much — all that anorexia and constant posing in front of a mirror, with nothing going on in their heads — and I’ve never been moved by watching them dance. I’ve tried. And I’ve seen Twyla Tharp and others of like fame.

Fascinating read. The inner game of dancers. Except for the iron discipline required, dancers are not so different than more normal humans. Raging hormones, romantic games, power trips, and all that.

miklos:

I guarantee that some dancers have a lot going on in their heads. (Some have too much, perhaps.)

I’m not a Tharp fan, by the way. Some of it is entertaining, but that’s about it

Where does “The Red Shoes” fit in?

I found the story rather repulsive when I saw the film, having been lured in by the dancing milieu.

All that Jazz movie dealt with issues of dancers, sex, and getting some work in return.

I think that might have been the secondary or co- drama of the movie.

I guess I should say, it dealt with those issues as part of Bob Fosse’s life, not per say In documentary style.

This inside account is a gem, Neo.

I was an accomplished ballroom and swing dancer for many years precisely because it was full of nubile young women who enjoyed being touched. Had a great time I tell you what. Now non-dancing SJWs are observing this scene and demanding new rules of etiquette intended to kill any dance passion. A good dance leader know exactly what women respond to and doesn’t need instruction from feminist clods who can’t even stay on beat.

As for modern dance it is pretentious and boring. True dance beauty comes from pattern and synchronization which modern dance hates and labels as uninteresting. Perhaps because modern dance exalts the ego whereas traditional dance are just about having fun with the opposite sex.

The question, it seems to me, comes down to the word “harassment”, its definition and its application. Harassment now means “unwanted”, which is quite a morph from its ‘formal’ definition. We live on shifting sands, rather like standing on the crest of a dune in the Sahara.

“Gay” used to mean something quite different, too, and being labelled “discriminating” was high praise of good taste, in my lifetime. Rogers Peet, a high-end men’s conservative clothier in NYC, used to advertise itself as being for men of discriminating taste.

“Gay” used to mean something quite different

It still does. Happy, joyful, and merry.

The alternate usage should be transgender (transgender spectrum or transgender spectrum disorder) or deviation from the masculine and feminine gender (i.e. physical and mental traits) closely correlated with the male and female sex, respectively. The modern, progressive (i.e. monotonic), or liberal (i.e. divergent) usage refers to males who exhibit a feminine or alternating feminine/masculine sexual orientation.

That said, humans are defined by a constellation of physical and mental traits, not limited to sexual orientation.

If ever there was an issue of our time epitomizing the metaphor “opening a can of worms.” this is it.

manningthewall.com

There seems to be a fine line separating attention and harassment.

No one that beautiful has any business being that smart, and vice versa. It’s just not fair. Diana Moon Glampers would not be at all pleased.