Free-climbing El Capitan

Yes, you read that right: someone climbed the monolith El Capitan in Yosemite without ropes, in what’s called a “free solo” ascent. That means crawling up the vertical rock face with only your hands, feet, muscles, and steely (some would say demented) nerves to help you along.

The man’s name is Alex Honnold, and you can read about his exploits in this NY Times article:

Alex Honnold woke up in his Dodge van last Saturday morning, drove into Yosemite Valley ahead of the soul-destroying traffic and walked up to the sheer, smooth and stupendously massive 3,000-foot golden escarpment known as El Capitan, the most important cliff on earth for rock climbers. Honnold then laced up his climbing shoes, dusted his meaty fingers with chalk and, over the next four hours, did something nobody had ever done. He climbed El Capitan without ropes, alone.

The world’s finest climbers have long mused about the possibility of a ropeless “free solo” ascent of El Capitan in much the same spirit that science fiction buffs muse about faster-than-light-speed travel – as a daydream safely beyond human possibility. Tommy Caldwell, arguably the greatest all-around rock climber alive, told me that the conversation only drifted into half-seriousness once Honnold came along, and that Honnold’s successful climb was easily the most significant event in the sport in all of Caldwell’s 38 years. I believe that it should also be celebrated as one of the great athletic feats of any kind, ever.

Also one of the great mental feats of any kind, ever:

Fear of falling is about as primal a fear as we humans have, and that fear is present to some degree whether you are 10 feet off the ground or 3,000. In this sense, Honnold’s specialty – free-soloing – is a distillation of the entire climbing world’s collective fantasy life. Vanishingly few elite climbers make careers out of free-soloing, and plenty call it irresponsible and deplorable, but in their heart of hearts they all recognize it as the final word in bad-assery…

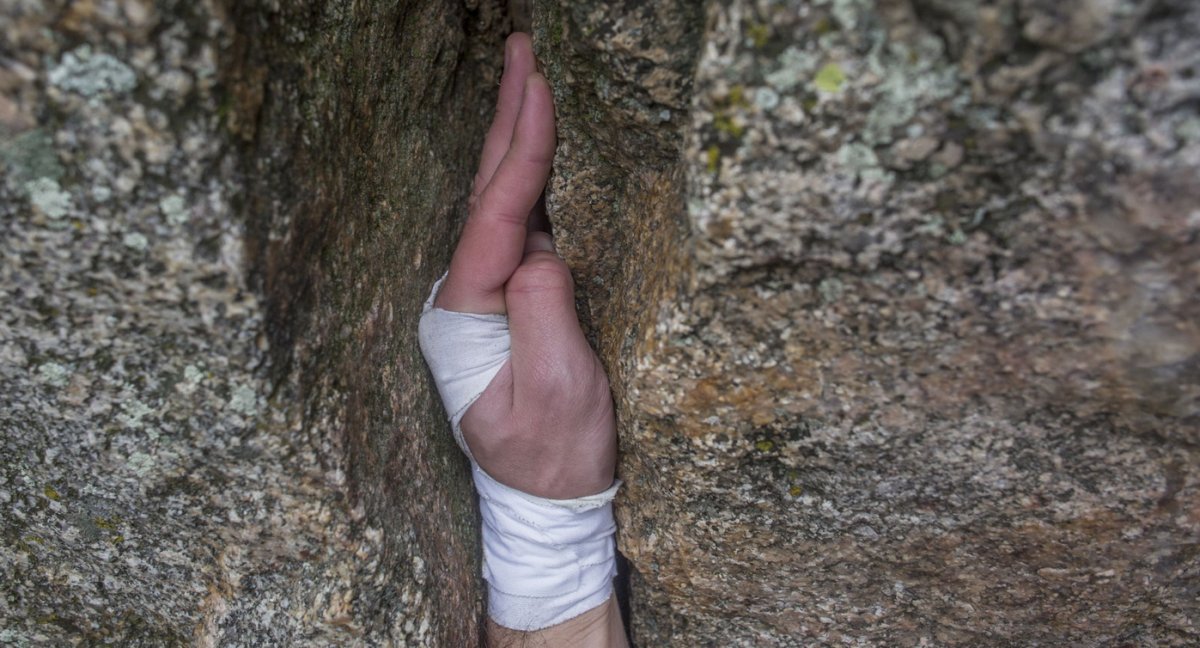

El Capitan does have vertical fractures that allow expert climbers to insert their hands and feet and sometimes entire legs and arms and then twist and flex those body parts in highly technical and painfully exhausting ways that do create a temporary grip over the abyss. Still, so much of that cliff is devoid of anything that normal human beings would recognize as handholds or footholds that the overwhelming majority of El Capitan climbers resort as I did to artificial aid. We insert hardware into cracks, clip nylon stirrups to that hardware and stand in the stirrups. Even then, we struggle to stay calm in an environment that feels like a mile-wide plain of smooth stone that we happened to be lying upon when it flipped to vertical and swung us higher into the sky than any of the world’s tallest skyscrapers yet reach…

…[T]he nature of the rock is such that no amount of finger strength can make it feel entirely secure. Much of the terrain is so smooth that it can be ascended only by identifying half-imaginary indentations, pressing shoe rubber against those indentations – smearing, as the technique is known – and then hoping that the rubber sticks while you ease upward.

Oooooo, sounds like fun, doesn’t it? NOT. But to climbers, and particularly to free-climbers such as Honnold, it’s a challenge they want to meet, and are confident they can and will meet.

I will pause now for a moment to post some photos I found here. This is only a small sample of what you can find if you click on that link, which I urge you to do. You won’t believe your eyes:

In case you hadn’t already figured it out, Honnold is different from you and me. I hate heights, so he’s particularly different from me:

Honnold’s sang froid on big cliffs is also so peculiar that even the world-class climbers who consider him a dear friend struggle to believe that it really is just sang froid and confidence, and not borderline-suicidal recklessness or at least a missing screw…[F]riends of Honnold’s joke that when Alex was a baby his mother must have stepped on his amygdala – the brain region that controls fear. Last year, fMRI testing at the Medical University of South Carolina tilted the scales toward precisely that explanation – an underactive amygdala, not a negligent mother – by confirming that Honnold’s fear circuitry really does fire with less vigor than most.

Sort of like those people who don’t feel pain, Honnold really doesn’t seem to feel much fear. But he feels enough of something akin to fear (or maybe it’s just the desire to live) that he’s very, very careful, practicing over and over with safety ropes until he knows the course cold and hasn’t fallen on any ascent for a long, long time.

My reaction to all of that is that of course Honnold’s brain is wired differently, as is true of most people who do extreme sports (although there’s a “which came first, the chicken or the egg” cause/effect question there). Honnold is one of the more extreme of the extremists. Ice water must run in his veins.

He is also—obviously—rather obsessive compulsive, as one must be to do that sort of thing successfully. Human beings can accomplish amazing feats if they have just the right combination of characteristics and all the stars are in alignment. He makes me think of wire-walker Kurt Wallenda, who said, “Life is on the wire, the rest is just waiting.”

However, Wallenda died in a fall from the wire after a lifetime of performing, and years after several members of his family were killed and some injured in a fall during the act in Detroit in 1962 (a roommate of mine had been present the night of the Detroit fall, and she told me about it and how frightening it was to be in the audience). Perhaps Wallenda just failed to retire at the right time, or maybe he assumed the risk and preferred to keep going.

But back to the Times article about Honnold:

Allow your mind to relax into the possibility that Honnold’s climb was not reckless at all – that he really was born with unique neural architecture and physical gifts, and that his years of dedication really did develop those gifts to the point that he could not only make every move on El Capitan without rest, he could do so with a tolerably minuscule chance of falling.

I agree with everything there until that last part—that Honnold’s chance of falling was “tolerably minuscule.” Obviously it was tolerably minuscule to Honnold; it depends on one’s tolerance. He’s the one who made the decision and assumed the risk, and he must have felt exceedingly confident. But that doesn’t mean his chance of falling was actually minuscule. I think it was certainly less than 50%, so that he was more likely than not to succeed. And of course we know that he did succeed.

This time. But I think that if, like the Wallendas, he repeated it often enough over time, he would probably die that way.

I wish him well. And maybe he’ll never do this again, having done it once (for his poor dear mother’s sake, I hope once is enough!).

I KNOW that gravity is not my friend.

In the novel, “Once an Eagle,” there is a character who is fearless. He is ultimately demoted as an officer because his fearlessness is getting his men killed. As captain Ahab said, “I will have no man in my boat who is not afraid of a whale!”

If this guy climbs alone, and if no one is below him to get squished, I have no problem. Eventually he will be killed and it will be a small loss.

My aversion to this is so great that reading this caused me physical pain in my joints. Stopped about halfway through.

Remarkable man.

I have been following Alex Honnold’s career with interest and astonishment. A former rock climber myself, I know the attractions of the rock. There is almost a sensual pleasure in putting together the pieces of a climb. Hold to hold, caressing the rock, moving smoothly as possible, exerting strength where necessary and always in control. Completing a difficult climb was always met with a rush of endorphins – Rocky Mountain High! So, I understand the psychology of how rock climbing can become an addiction. Honnold is addicted to it and to his need to control himself. He has both physical and mental gifts that are perfectly suited for the sport. Four hours to climb El Cap. Most people, even well conditioned rock climbers, are not aerobically capable of such a feat, much less have the muscle strength.

I have done some climbs in Yosemite. Mostly of the trade route variety. My skills or commitment never reached the level of El Cap or the NW Face of Half Dome. I often soloed but never on long climbs that were at the limit of my ability, as Honnold does. My self preservation instincts would never allow me to push my limits like that.

I hope he feels he can dial it back now. I hope he lives to be an old armchair climber like me. I fear he will not.

Catherine Destivelle – Awesome free solo climbing in Mali

Look mom, just me.

Just her wits… and a lot of courage.

No envy. Maybe a little.

I was a rock climber in my younger years and made an annual pilgrimage to meet up with a boyhood friend to climb the rocks at Vedauwoo, WY. Mrs parker insisted I stop after a minor injury from a fall back when I was 49. So I took up skydiving and still jump about 20 times a year. It never gets old. Every time I jump I want to go back up as soon as my feet hit the ground.

I have a son who climbs. I don’t like it at all but not as much as his whitewater kayaking

mezzrow, me too, me too. My knees hurt, or ache, or weaken, or fail, or something so intensely that I can barely look at the pictures.

I had an old friend who was a rock climber. Decades ago, he was climbing with a friend, and somehow they both fell. His friend died, and my friend sustained a brain injury that has altered his life ever since.

I was already afraid of heights before that happened. Now, I just don’t do heights at all.

Mrs Whatsit,

Do a tandem jump at 15,000 feet and I promise your fear of heights will turn to joy. Then you will desire to go through the training to make solo jumps. It is beautiful up there and tranquil.

This reminds me of the steely nerves it takes to stand over a 6 foot putt on the 18th hole with everything riding on it, the whole world hushed as you perform that simple movement. It seems to me that the nervous system is not apart from one’s physiology and begins to degrade after 35-40 years of age.

Honnold, at 31, is at his peak (no pun intended). Let’s hope he is wise enough to know when to back off, though it wouldn’t surprise me if not.

For us mortals . . . I took a couple days off in May to go up to Yosemite and see the waterfalls since this was a heavy snow year. I walked up the 4 mile trail and back down via the Panorama Trail and it was stunningly beautiful. I never tire of God’s Temple.

No Fear. You haven’t lived until you defy death.

Here’s a link to a brief article in the NY Times about ditching your fears. I like the napkin sketch from Will Smith which says it all.

https://www.nytimes.com/2017/04/24/your-money/six-steps-to-ditching-your-fear-and-starting-that-big-thing.html

I imagine he had climbed the route up the face literally dozens of times to the point he probably could have done the climb in his sleep. Sort of like how a pianist plays a very difficult piece.

I can understand why Honnold did this. When I was his age I had what I call my “Summer of Living Dangerously.” Three times death came very close to me. Three times, I reacted quickly and properly enough to keep it at bay. There’s a thrill that comes with meeting danger and defeating it.

At the end of that summer, I pondered what I’d done and concluded that, if I kept up like that, eventually the odds wouldn’t be in my favor, that my reactions would be a little too slow. I quit climbing and turned to hiking and biking. Of course biking in Seattle city traffic has dangers of its own.

Gravity is a harsh mistress.

I climbed starting at 16 and continued until 31–my age when my first child was born. I definitely knew fear on many climbs–and fell plenty of times while pushing my limits. Fortunately, with generally few ledges and, instead, massive slabs broken by crack systems, Yosemite crack- and face-climbing routes are relatively forgiving of falls–if you are using a rope. Back in the 1970’s when I did most of my Yosemite routes, we wore neither helmets nor harnesses (which better distribute the force of falls on the body). Just “swami belts” of nylon webbing wrapped many times around our waists.

Part of what drew me to climbing was definitely the physicality and mental challenge, so I can honor Honnold’s feats even while knowing that all the great free soloists have ended up with lives shorter they would otherwise have been. He is an alien and I wish him well.

Is there a word for “lack of fear of heights”?

After a summer of guiding novice climbers and free climbing up to 5.11 with friends, I free soloed a 5.7 (easy-moderate) route, about 400 feet, at Table Rock at Linville Gorge. I had done this route dozens of times, and it was well in my skills-and-experience base. I was expecting an adrenaline rush. But it was not much different from the slight concern you get when climbing a ladder. Still, though it happened 30 years ago, I remember with vivid detail a number of moments from that climb.

Now, I’ve pretty much hung up my climbing shoes…

Gravity. It’s not just a good idea. It’s the Law.

I see two separate topics here: 1) fear of heights, and 2) compulsion to do dangerous actions.

Working construction, I felt that fear of heights. It seemed irrational because I thought, If I am standing of the edge of a sidewalk, how likely am I to fall into the street? As a young construction worker, I realized I got comfortable with heights quickly while others stayed scared. When I was drafted for the Vietnam War, i volunteered and became a paratrooper. After the Army I was attracted to rock climbing because it took a boldness that I was comfortable with. I could excel at rock climbing and mountaineering. Yet, when I drove to the Grand Canyon after two years of rock climbing i was surprised to feel that old fear of heights. But, after hanging out at the rim for 15 minutes, I felt back to my usual confidence.

In discussion about Honnold’s stupendous ascent, I found this discussion of that overwhelming fear of heights, which most of us fear: https://braindecoder.com/post/whats-behind-call-of-the-void-and-the-urge-to-jump-1299814876

The other issue i raise is the compulsion to voluntarily engage in risky behavior.

In 1980 I was on a Mt. McKinley summit attempt with Jim Wickwire and Lou Whittaker. In 1978 Jim Wickwire was the first American to summit K2, but he almost died doing it, having to bivouac at 27,000 feet. A few years after my McKinley experience, Jim Wickwire endured yet another mountaineering tragedy, which was back on McKinley. That prompted him to write Addicted to Danger, which is the best mountaineering book I have ever read. Bold adventurers get addicted to the acclaim they get. That can be true whether they are getting widespread recognition or just recognition from a small group of friends or even just their own internal voice bragging to themselves.

I hope that Honnold learns a lesson from John Bachar. Bashar was the first to make a big name for himself as a free solo climber. He fell to his death from a free solo on Dike Wall in the Sierra Nevada at age 52.

Now, I am pleased with what I achieved in the mountains and glad I didn’t try to achieve more.

Nothing to worry about. Gravity is the weakest of the four forces. Electromagnetic force is much stronger than gravitational force. If you were a charged particle in an electrical field, you might be in serious danger.

Simply Awesome! A magnificent accomplishment!

I get worried once I go higher than the third rung on a ladder.

I remember when 60 Minutes profiled that dude a few years ago. They filmed him doing another vertical cliff in Yosemite. I needed a shower after watching it I was sweating so much. Dude’s not normal.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NKAloYst7p8

A must see documentary for those interested in Yosemite climbing is “Valley Uprising.” Honnold is featured at the end.

I had also seen a very minor documentary about sky-diving and BASE jumping where they modeled the enthusiast’s progression as an addiction. The focus of that story was a young man who’s father owned a jump school and had started jumping at age 10 or 12. By his late teens he had progressed to very extreme BASE jumping and became paralyzed from the waist down in an accident. Or should it be called an incident?

The man who held many records at Yosemite prior to Honnold was Dean Potter. He had done a tandem speed climb of El Cap in 2.5 hours and solo climbed both El Cap and Half Dome in a day. He progressed to BASE jumping with a bird suit. The biggest thrill there is flying close to terrain which is crazy dangerous. He met his demise in 2015 trying to fly between two rock towers in Yosemite.

The data on Honnold’s fMRI scans could indicate a genetic or physical pre-disposition towards fearlessness. Or it could represent the end result of more than a decade of mental training.

As Mel said, if you have never hiked the Mist Trail up to the top of Nevada Falls in Yosemite, it should be on your bucket list. Go in the spring or early summer after a wet California winter and the this monster falls will be raging. Bring rain gear as the “Mist Trail” will be deluge of horizontal rain coming from the impact zone of the falls. DO NOT swim in the stream up top as very many have died doing so.

Sorry, but climbing without any sort of safety equipment just screams death wish.

Years ago I remember seeing a video of a free climber doing what seemed impossible. This post reminded me of it, and I think this is the video of the portion of the climb. The guy was Dean Potter, at the time on of the top climbers. Apparently he was killed a few years ago in a base jumping accident. I wonder what the life span is of these kind of people?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8zyZvEBuw_4

You’d think the enormous brass balls inside those jaunty climbing pants would weigh him down but you’d be wrong.

John Muir on Mt. Ritter, by Gary Snyder

After scanning its face again and again,

I began to scale it, picking my holds

With intense caution. About half-way

To the top, I was suddenly brought to

A dead stop, with arms outspread

Clinging close to the face of the rock

Unable to move hand or foot

Either up or down. My doom

Appeared fixed. I MUST fall.

There would be a moment of

Bewilderment, and then,

A lifeless rumble down the cliff

To the glacier below.

My mind seemed to fill with a

Stifling smoke. This terrible eclipse

Lasted only a moment, when life blazed

Forth again with preternatural clearness.

I seemed suddenly to become possessed

Of a new sense. My trembling muscles

Became firm again, every rift and flaw in

The rock was seen as through a microscope,

My limbs moved with a positiveness and precision

With which I seemed to have

Nothing at all to do.

From “No Nature: New and Selected Poems” by Gary Snyder (Pantheon: 392 pp., $14 paper)

I determined a long time ago that the only way I could accurately determine the limit I could safely push myself to would be by experimentation.

I decided to stop experimenting after a couple crashes.

I highly respect LEO, Fire/Rescue and combat veterans who find a venue that allows them to transcend their limits with a concurrent value to society.

Pingback:Long Read of the Day: El Capitan, My El Capitan - American Digest

As noted above, learn to sky dive, it will set you free. Once you have done it it you will be free. Noyjing beats free faling.

How did he get down?

Groty: “Dude’s not normal. ”

Colby Cosh (IIRC) once used the word ‘mutants’ for these people. He wasn’t being insulting – just pointing out that top level competitors aren’t like the rest of us.

no problem, they’ll be back at the last day.

Very, very interesting posting, Neo. Especially the part about the unusually low physical fear-reaction (and also pain-reaction) in the brain. Thanks. :>)