The latest scary virus: Zika

It’s not really new; the virus and the disease it causes, Zika fever, was identified back in the 1950s in Africa. But it has been spreading for a while, and recently made the leap to the Western Hemisphere and is causing trouble in Brazil, according to scientists:

Zika virus is transmitted by daytime-active mosquitoes and has been isolated from a number of species in the genus Aedes…

Before the current pandemic, which began in 2007, Zika virus “rarely caused recognized ‘spillover’ infections in humans, even in highly enzootic areas”…

In 2015 Zika virus RNA was detected in the amniotic fluid of two fetuses, indicating that it had crossed the placenta and could cause a mother-to-child infection. On 20 January 2016, scientists from the state of Parané¡, Brazil, detected genetic material of Zika virus in the placenta of a woman who had undergone an abortion due to the fetus’s microcephaly, which confirmed that the virus is able to pass the placenta.

For most people, a bout of Zika fever is a mild event with no lasting consequences. The fear that’s now spreading is that some scientists believe that Zika is connected to a dramatic spike in microcephalic births in an area of Brazil where the virus has become common:

In Brazil, as thousands became infected with Zika, the rate of microcephaly increased exponentially. In 2013 and 2014, the country documented 167 and 147 cases of microcephaly respectively. But by 2015 as Zika spread, Brazilian officials registered 2,782 cases before the end of the year, according to the New York Times. That’s a 1,792% increase year on year. Virologists who studied Zika in Brazil said they have “a lot of indirect evidence” that connects the virus to microcephaly.

The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has said there is no direct link yet between the virus and the birth defect. Nevertheless, the CDC warned pregnant women to avoid travel to countries where Zika is present, and unofficially some Brazilian health authorities have warned women against getting pregnant.

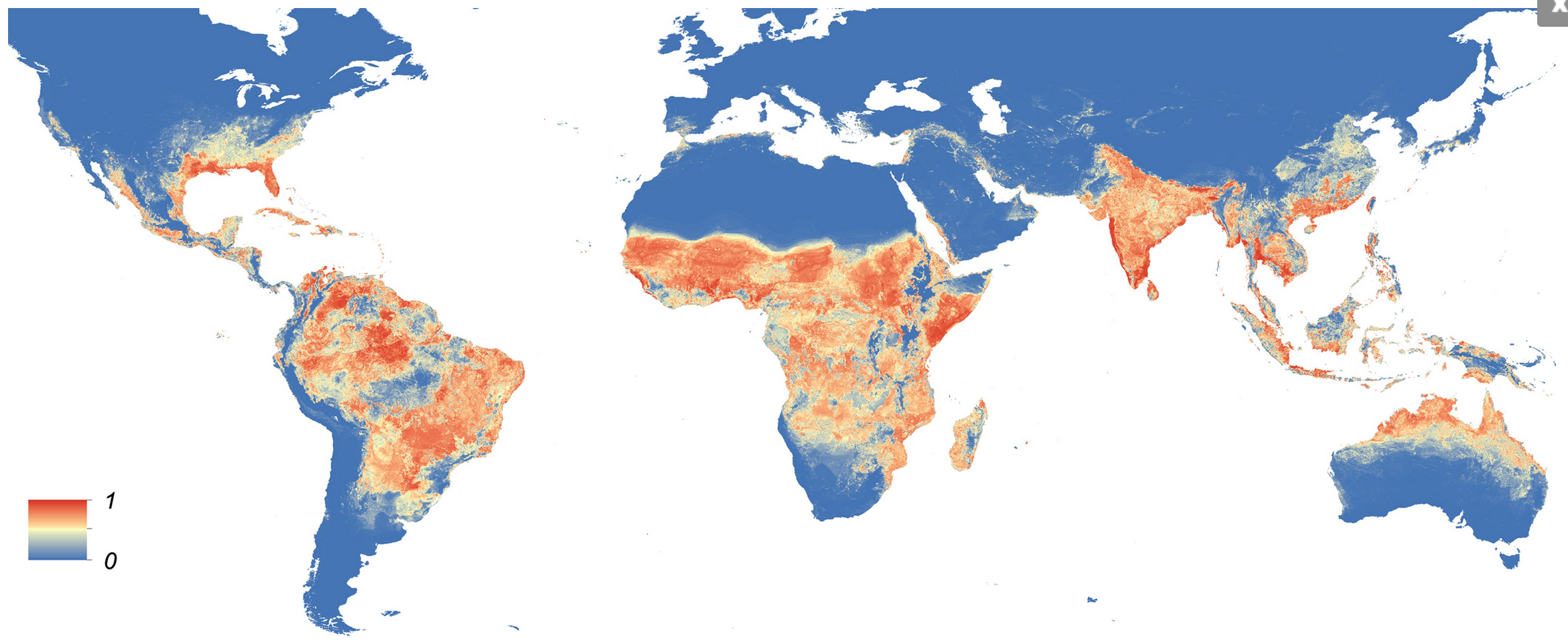

So although it has not been proven, there is a statistical and geographic link. The mosquito is not yet in most of the US, but at present is estimated or projected (it’s really unclear what this means) to include areas of the southeastern part of the country and along the coast about as far north as New York:

A vaccine is many years away.

I have no idea whether this will end up being a big deal or not. It’s certainly a big deal when a family has a microcephalic child, and although the link is not proven, those figures are certainly indicative of a strong possibility.

I’ve read a lot of articles about this, and I’ve not seen one that mentions DDT as a way to combat it. And yet it seemed to me it could be a good stopgap measure. However, when I checked about the mosquito in question, it seems that some strains are resistant to DDT.

[NOTE: I’ve written previously about DDT in connection with malaria.]

There is another way to solve this.

XON.

I remember when West Nile Virus first came to the USA. An infected passenger from Egypt came to NYC and was bitten by mosquitos. Birds are the primary victims and they can spread it fast. Rudi Guliani (a real tough guy) was Mayor and he rapidly dosed the whole city with anti-mosquito sprays.

But the wealth gold coast of Connecticut (Greenwich, Fairfield etc.) squawked loud and hard about anything but the least offensive spraying in their marshy shoreland.

I’m not sure if intensive spraying in CT would have stopped the spread, but we’ll never know.

The CDC was started in part to control malaria, which is why they are in Atlanta. http://www.cdc.gov/malaria/about/history/elimination_us.html

Most of this reduction was done prior to DDT and involved draining swamps and other mosquito breeding grounds. These are protected wetlands today, so DDT is more important than ever

I see a slice of projected occurrence in the Central Valley of California. I don’t think I need to spell out to the readership the source of this.

Wife and I are on a cruise. Just now leaving San Juan headed to St Martin. They are telling us to use deet, wear long pants and long shirt sleeves.

Isn’t it time to eradicate the mosquito from the world? Scientists cannot identify any ecological function for this horrible beast. any arguments to the contrary are very poorly thought out and not supported by data. DDT and other conventional or biological insecticides are not the answer, however. Our future salvation will be found in biotechnology (genetic modification). The solutions are in the labs now, believe it or not.

We have big brains. Let’s use them.

Neo, Know anybody at CDC? ask them whether or not this is an STD. ask them “off the record”. see what they say.

I am with you on the use of DDT. Even if some mosquitoes are resistant, I think we need to eradicate as many mosquitoes as we can.

Lurch, the ecological function of mosquitoes is well known for decades: without them no forests could survive for long. The essential nutrient for plant life, potassium, is very soluble and is quickly washed from soils. All this flux of potassium goes into ponds, lakes and rivers, and eventually into ocean, and the only species which can recover it from water bodies are mosquitoes. Adult insects do not eat anything except sugar (males) and blood (females) and don’t grow. All growth and so potassium intake is made by larvae in water. Adult insects die elsewhere and return potassium into forest ecosystem, making potassium cycle closed.

I must add that many species of birds are also totally dependent on mosquito as food source, and their numbers in forests will drop significantly without this food. This will result in explosive population growth of leaf-grazing caterpillars, whose numbers are controlled by insect-eating birds. Forests will die quite quickly. This is not a speculation, but experimentally proved fact. In early 70-es a new scientific center was built near Novosibirsk, so-called Akademgorodok, surrounded by taiga (boreal forest). But life here was almost impossible because of huge numbers of mosquitoes and gnats. So the bosses of the center sprinkled the forest by insecticides (DDT-like chemicals). This resulted in silent spring – not because DDT was toxic for birds (it wasn’t), but because the birds could not feed their chicks without mosquitoes. The next year all the forests around the city was destroyed by Siberian silk-worm, all leaves eaten away. It took decades to restore forests and keep mosquito populations around buildings under control by less devastating methods.

references, please. The potassium cycle has nothing to do with mosquitoes, other than a minor contribution as any other animal may have. One could argue that some birds and bats eat a fair amount of mosquitoes but these animals could easily find other food sources. The ecological niche mosquitoes occupy would soon be taken over by another aquatic species. Nature abhors a vacuum.

No, the mosquito has very limited ecological impact and in fact, they are not indigenous to most of the ecosystems they infest. they would be missed as much as small pox is missed. In no way are they keystone species, unless you feel the need for human population control and suffering.

It is time to begin eradication of at least some species. But, hey. If it makes some people unsettled to “play God”, we could always keep a few colonies going in Antarctica or in space, just for old time’s sake.

My mistake: I meant phosphorus cycle, not potassium. What is certain, that biomass of mosquito larvae in Arctic tundra lakes and boreal forest lakes is 1000 times bigger than of any other species. That is enough to make them absolutely necessary for these ecosystems, as foundation of food pyramid. These species emerge in Jurassic period, more than 175 mln years ago, and all subsequent life evolved on this background. Nobody else can eat small organic particles going into lakes, so the very existence of the lakes filled with fresh, clear water depends on these larvae as filtrators and consuments of humus. Smallpox is very recent virus, several centuries at best. it plays no role in ecosystems.