Losing your turns

[NOTE: I thought you might enjoy a recycling of this old post, as a palate cleanser.]

What’s a pirouette? Here’s the Wikipedia definition—and, as a former dancer, I can attest to its correctness:

What’s a pirouette? Here’s the Wikipedia definition—and, as a former dancer, I can attest to its correctness:

One of the most famous ballet movements; this is where the dancer spins around on demi-pointe or pointe on one leg. The other leg can be in various different positions; the standard one being retiré. Others include the leg in attitude, and grand battement level, second position. They can also finish in arabesque or attitude positions. A pirouette can be en dehors – turning outwards, starting with both legs in plie, or en dedans – turning inwards.

The definition may seem Greek to you (actually, of course, French) but to me the terms are as familiar as English. The terminology of ballet, repeated to me from the age of four till my late thirties, when I quit dancing, gets drummed into the brain until it becomes reflexive.

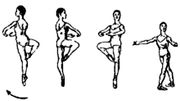

The diagram, for instance, shows an en dehors turn, since the dancer is spinning in the opposite direction from the leg supporting her weight, and her other leg is held in the postion known as passe.

But I’m not here to teach you dance–fortunately for both of us, since that would be quite a trick, online. I want to talk about the psychological phenomenon every dancer knows about, which is known as “losing your turns.”

All of dance is hard for the dancer, although it’s incredibly satisfying and rewarding, a completely absorbing meshing of the physical, musical, artistic, and spiritual. But turns are notoriously hard for most people.

Certain people are different, however; they’re that rare phenomenon known as “natural turners.” Some strange trick of brain and inner ear, some unusual sense of centered balance, allows them to turn easily almost from the moment the step is first introduced to them. Natural turners almost never lose their turns; but the rest of us not only have to struggle to learn to turn, but are acutely aware that the knack can be lost.

Every person has a preferred side to which turning is easier, almost always the right. There have been only a few famous dancers who are/were “left-turners” (the extraordinary Fernando Bujones and the elegant Anthony Dowell come to mind), so most ballet choreography features turns to the right. The favored side for turning has no relation to handedness, by the way; it’s an entirely separate issue (I’m left-handed and a right turner, for example).

So the way the brain is structured is definitely part of what makes turns easy or hard. Turns are also especially challenging because, more than any other part of ballet, they require strength and relaxation in almost equal measure. Tension is a great turn-killer, especially tension of the head and neck, which have to work together to move fluidly in the manner known as “spotting” in order to avoid getting too dizzy (spotting involves keeping the eyes on a single “spot” until the last moment of the turn, and then whipping the head around quickly to come back and focus on that object again).

The best comparison I can think of is to baseball: the batter’s swing and the pitcher’s curve ball. Both are notorious for disappearing for unknown reasons, sometimes for a long time (sometimes ending a career, actually), and then mysteriously reappearing. When a batter loses his swing, he works with a coach, trying to locate the problem, fine-tuning things till it returns.

Likewise with dancers. You can see them practicing their turns after class, over and over and over, looking in the ever-present mirror to see if they can detect that elusive flaw that’s spoiling their turns. Because when turns go, it’s not a pretty sight. Balance is a thing that’s either on or off; a person who could once do four flawless revolutions from a single push-off preparation will now have trouble getting around twice—perhaps even hopping to complete the revolutions or, (for a female) falling off pointe, which can involve an ignominious and dangerous pratfall.

Virtually all dancers know that losing one’s turns is a possibility every time they take the preparation for a turn (usually a momentary pause in fourth or fifth position with the knee bend known as a demi-plie, eyes fixed on something ahead for the “spotting,” arms poised to whip and then close in for a bit of added impetus [see instructions]) . It’s a leap—well, not exactly a leap—of faith, a push into the unknown. Will the turn hold? The dancer has to have the confidence that it will, and relax into it, bringing together all his/her technique and knowledge without really thinking about it. It’s part of the dancer’s body memory, and trust has to enter into it.

Strangely enough, writing a blog has some aspects of this process, too. No, it doesn’t have that element of physical release–au contraire, it’s physically quite static. But every day, or even several times a day, the blogger faces that blank screen and has to take a little preparation and push off, assuming the turn (of phrase) will come. It’s different from other types of writing, because there’s so little time to prepare, and even less time to polish. One must produce at a fairly fast clip, digesting the news and what’s being said on other blogs (sometimes swallowing whole without chewing enough) and then saying one’s piece.

I’m not complaining; it’s a self-imposed labor of love. Sometimes I face that blank screen with eager anticipation—I’ve got an idea, the words flow, and the thing practically writes itself. A quadruple turn, as it were. Other times I cast about for something to say, or I have an idea but my thoughts are hard to sort out, or I realize that to do justice to the topic I’d really have to write a small book. Sometimes the product is only so-so; sometimes I’m just hopping around and fall off pointe. But the next day I usually return to take my place again, make my preparation, and try to relax into the turn with confidence. And, if it doesn’t turn out quite right, I try again the next day.

Fast and furious:

Or slow and controlled:

Golf too has a couple of these: one is known as the “yips”, the other (as demonstrated in the film “Tin Cup”) is called the “shanks”. Both are evil.

I only danced for a little over nine years. I was okay — I could do it, and people who didn’t know better thought I was graceful. I was adequate at turning. Only could really do enjoy dehors right turns.

But loving ballet, and having danced for almost ten years, is why I get frustrated watching floor gymnastics. I find them pretty uncontrolled and lacking grace. Ballet dancers are no less athletic and no perform extremely difficult moves, but they have control over every part of their body. Gymnasts lack that control. I blame Nadia Comenci.

https://ymarsakar.wordpress.com/2015/11/20/rousey-ronda-no-longer-undefeated/

Off topic, some vid links about the Ronda Rousey action.

“I’m left-handed and a right turner….”

In more than one sense of the words.

Real men don’t pirouette. Dem politicians like Rahm? I guess he found ballet or something extremely satisfying and rewarding.

Oh, how I love to watch fouettes! I need to go to a ballet soon!

Well, Neo, I seem to have successfully understood another of your posts about dance. And on a Saturday evening, no less. That felt fulfilling.

The things that struck me particularly about this post were your uses of analogy to make points on two occasions (baseball and blogging). With my chess students, I teach by analogy quite a bit. This works especially well with those of my students – and there are several of these, which is to be expected given the age range – who follow pro soccer and play for their school teams themselves. I pull in things from my own soccer-watching to which they can relate. So even though I don’t have enough baseball to really get your allusion to a batter’s swing problem, I can still get the gist (what a curious little word, ‘gist’ – would be fun to see your riff on its etymology).

Those turn examples were very appealing. It’s interesting how the free leg is used to make those in-out movements to renew the momentum. It would be fun to see from above and then trace out the path drawn by the foot. Do you remember Spirograph? I mean the drawing toy. You could make those wonderful circular patterns depending on the sizes of the gears that you chose. From above, I suspect the dancer’s free foot would trace out paths much like those.

Conservation of angular momentum!

Have you watched the new tv series that revolves around ballet?

Philip:

To make it even more complicated, there are two basic ways to do the fouette. The first one has fallen out of favor, but basically it just throws the leg out to the side rather than whipping it around, and so you don’t get as much momentum but it’s fast. The second, much more popular more modern way, is to have the leg go to the front, after a turn, and then whip it to the side, giving the dancer a lot of momentum.

Inside baseball 🙂 .

Artfldgr:

Yes, I watched the first episode. It was incredibly offensive. The dancing was fine, the plot and characters soulless and decadent.

Place not your faith in principalities or powers, Neo, especially of the Western Hollywood media sort.

Neo:

Does the ballet pirouette use the same technique as the spin move that Michael Jackson did on most of his videos? I always wanted to learn that one myself.

I’m not sure I understand, but it sounds a bit to my like something I’ve experienced ice skating. I ice skated a bit as a kid but my family couldn’t afford skates (my sister and I shared a pair of ill-fitting, hand-me-down, ladies figure skates) and we certainly couldn’t afford ice time, but the fire department would sometimes create “public” rinks in some of the city parks.

In my mid-30s I had a chance to play ice hockey twice a month and found I really enjoyed it, so at that relatively late age I started trying to learn to skate well. Since I lived in Florida I bought a pair of roller blades so I could practice without paying for ice time. I got to be a decent skater (but I could never master stick handling). When my kids got old enough to learn I tried to teach them and that’s when I realized I had no idea how I was skating backwards.

As you describe with ballet turns, it just somehow happens. I’d try to explain to my kids what my feet or legs or specific muscles were doing, when, but as I tried to dissect it I realized it was a lot more of an idea than an action. It seemed mostly mental (at least when going backwards from a standstill). I’d think the thought and I’d start moving backwards. And, as you mention with turns, I do know there have been a few times where I was standing still in skates and willed myself backwards and nothing happened.

Oddly enough, not long after taking up skating I found myself doing turns sometimes when standing around. I distinctly remember waiting in a store while my wife was in the dressing room trying on outfits. There was a mirror there and no one was around and I stood up on one foot and turned. It wasn’t a spin. It was a turn. I couldn’t recall ever doing anything like that before. I did it again, and again, slow, fast. I tried to break down how I was doing what I was doing and I remember specifically noticing that it felt like skating backwards; it wasn’t so much of a series of physical actions with my foot and leg muscles, I just sort-of thought to turn and I did.

Before typing this I stood up on the hardwood floor of my kitchen and you’re right, I do turn to the right. Interestingly, when learning how to turn in ice skating (either completely, or half-way, finishing moving backwards) I noticed it was much easier to do to my right than left, although I practiced the left just as much so I would be able to turn both ways in a game.

My guess is my “natural” ability to turn on one foot is a direct result of learning to skate. I imagine I would have never stumbled on to it had I not learned to ice skate first.

I have asked other people who skate to describe skating backwards from a standstill and have yet to find anyone who can specifically explain what they do. There doesn’t seem to be a specific action one can discern.

I’ve noticed a corollary with music. I can usually sit at a piano and pick out a melody. It varies by song; some are easier than others. A few years ago I decided to try to formally learn to play. Interestingly, as I learn more and get better at reading music my ability to play by ear sometimes disappears. When I sit down to play with no sheet music, in front of anyone but my immediate family, I usually have a moment of panic, “what if it’s not there?!”

I don’t seem to have a clue how I play by ear and so I don’t have a clue what to do when I can’t, and the more proficient (the more “conscious” I am of what I’m doing) the more often I stumble (the “subconscious” component dwindles). Songs I’ve memorized from sheet music are always there, but the “ear” part sometimes disappears.

Interestingly, as I learn more and get better at reading music my ability to play by ear sometimes disappears.

The same applies to martial artists learning new techniques and schools. A natural athlete can do certain moves almost sub and unconsciously, but when asked to verbalize what they are doing or to slow it down, they forget because now they are conscious of it.

The conscious mind is a crutch at times. It is using the frontal cortex, the visual and logical cores, to process information. It is very slow and resource intensive to do things in that fashion. Parts of the mind and the neural system that operates subconsciously, are extremely effective, but the conscious mind does not understand how the black box works. Only that you get benefits from it, results, like the ear for music. You don’t see what’s inside the box, only the inputs and the outputs. It’s a black box, a machine that you don’t know how it works.

The conscious mind exposes the inner workings, by figuring things out and connecting the dots.

Normally after 10-20 years or 10,000 man hours, the conscious mind can integrate with the subconscious skills. Meaning if you spent 1000 hours learning to read music visually, and 1000 hours learning to listen to the same music by ear without the eyes, producing a training program of 4 hours conscious, 4 hours by ear per day, you would be able to have the “brain” connect the two areas together eventually later. Until eventually, you can run those mental cores in parallel, at the same time.

I have asked other people who skate to describe skating backwards from a standstill and have yet to find anyone who can specifically explain what they do. There doesn’t seem to be a specific action one can discern.

It’s two different skill sets there. The doing and the teaching. Most people have not mastered both, nor even one of them.

The motor controls in the brain stem and down the spine, control movements. The “conscious motor controls” in the brain is an illusion, so to speak. If you consciously tried to control all the muscles, little and large, in your leg as you walked or run, you might fall down. You can’t make the adaptations quick enough consciously.

The conscious part of the brain just sends an intent to the motor brain stem and spine to “do x”, and the action is done semi autonomatically. The only part the conscious mind needs to be aware of is the result, how well the action is performing. If it is performing well, the conscious mind thinks it is “controlling it”. If it is not performing well, the conscious mind will “intercede” and change something. It’s like a CEO that thinks he is managing and micro managing everything in his business. Since that’s impossible for complicated systems, somebody is wrong.

Rufus T. Firefly, Ymarsakar:

That’s the differences between dancers/skaters and teachers of dance or skating. The latter have to know how to break down the movement and convey how it’s done to novices.

neo-neocon The same thing for people who don’t know how to roll when falling forward and down. I explained it using sequential steps and maybe a video, since I couldn’t demonstrate it myself. Others explained it “you just do it”, because to them that was how they did it.

Ymarsakar,

I think I understand what you wrote, but in the two instances of playing by ear and skating backwards from a standstill it’s a bit different.

Regarding complex sequences of physical action, I’ve heard it described as, “the dancer doesn’t know all ten thousand actions by memory, they only know which follows which.” To correlate to the piano; the classical pianist doesn’t necessarily have all 100 thousand finger combinations in a piece in her brain, she just knows what notes follow the notes she just played. I agree with that. That’s how such things seem to work to me. A golf swing is a good example; break it down into components and drill little parts, then connect them. That’s also how I memorize written music; in chunks of measures.

But playing by ear is something different to me. I honestly don’t know what I’m doing. I can’t even piece it together. It’s either “on” or “off.” Skating backwards is a similar thing. One second I am standing still, the next I’m moving backwards with no discernible muscle movement. I can explain how I skate forward from a standstill, but not backward.