Cartoons and me

When I was nine or ten years old I was given an individual IQ test by a family friend who was getting her PhD in child psychology, and having to administer the test to a certain number of children was part of her training. No one told me the name of the test (my guess is that it was the WISC), but it took quite a while to take and was rather fun, because unlike pencil-and-paper tests it involved a lot of give-and-take between us.

It’s funny how well I remember the test after all these years. Part of the strength of the memory was the fact that the test didn’t resemble any others I’d ever taken before. In later years I recognized some of the question types—for example, those thought problems where you had to ferry some combination of potentially incompatible things or animals across a river in a boat, and you could only make a certain number of trips.

I don’t think in those days they actually informed kids of their IQ scores, although I have some vague recollection of having been told I’d done very very well indeed on the entire exam, every single part of it—that is, except for one subset of the test. I don’t know what that part was called, but I know it involved cartoons.

Cartoons were already my nemesis. I didn’t like them, although they were ubiquitous on TV. I didn’t like watching the creature being flattened and then springing back up again. I didn’t like the characters walking off cliffs and not realizing it for a moment, and then falling. I didn’t like the pummeling and the mayhem; I felt it as more real than I knew it should be perceived. And in some strange way I sometimes even had trouble following the plot.

Was that because I wasn’t interested? Or was it because I was repelled, or because I was particularly cartoon-challenged? Probably a combination of all three, because the phenomenon persisted into adulthood and involved even some cartoons whose content didn’t especially repel me. I used to like animated Disney movies, but have never liked Pixar, in part because the images seem “wrong” to me in some difficult-to-define way.

Sometimes there’s too much going on visually in cartoons, too; I get distracted. I sometimes fail to get the joke in non-animated cartoon squares (like the ones in a magazine) because I focus on the wrong detail or misinterpret details in odd ways.

This problem doesn’t seem to beset me in life or in any other form of humor; it seems limited to the world of the cartoon. I probably “get” most of them in the end, but it can take longer than I think it should. I tend to lose patience with them, too.

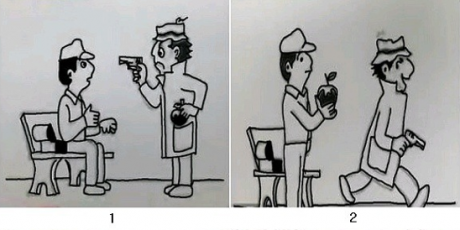

My difficulty on that subset of the long-ago IQ test didn’t surprise me in the least even then, because I’d already perceived those questions on the exam as having taken me longer to answer than the rest, and/or I’d resorted to guessing. That section also had contained more exercises that I’d finally decided to give up on because they seemed insoluble to me. The format was that I was given a series of small stacks of cartoon drawings, each set containing perhaps five drawings in all, and I was supposed to put each pile in chronological order as in a comic strip and then tell the tale of what was happening.

The pictures started out easy, but after a short while the each group seemed very confusing. What was I supposed to pay attention to? Was the man coming or going, and why? Was he sitting first and then standing, or the other way around?

On thinking about it now, I did a search for the phrase “IQ test put pictures in order” and sure enough, up popped something similar to what I remember. And sure enough, it also gave me a headache almost immediately just to look at the page and make the effort, even all these years later.

According to the text, this cartoon-ordering test is solved by college students on average in about a minute. Not by me. How about by you?

There’s something so off-putting about it that I almost can’t look at it, the pictorial equivalent of trying to unscramble a series of nonsense words or listening to an orchestra tuning up for too long.

All of the preceding was a very roundabout way of explaining why it was that this New Yorker article about how we perceive cartoons was of special interest to me, especially this part of it:

“It’s a holistic thing,” Restak said. “You can’t just look at one part of this picture. If someone has what’s called simultagnosia, they look at this and say, ”˜Oh, it’s a boy trying to steal a cookie!’ ” He described the parts of the brain that help people comprehend such things. “The occipital, that’s where the cartoon is seen. The parietal gives you the ability of seeing the whole picture. And here’s the important part for the cartoon: the temporal pole. It contains perhaps hundreds of thousands of scripts, or schemas”¦. This is the occipital area; this is the where. In the diagram I showed you, the picture of a kitchen, it gives you the whole totality of it; it tells you what the things are: the dishes, the water, et cetera. The dorsal, which is this part on top, is important for scanning the cartoon, what scripts are being evoked, what’s coming out of the temporal pole. This all occurs before reading the caption.”

I looked up “simultagnosia,” and I don’t have it. Fortunately, I’m not that bad. But something’s going on, although I had no difficulty understanding any of the cartoons in the article.

I’ve always rather liked those single-frame type of cartoons, though (unlike comic strips or animated ones), especially if they have captions. Captions seem to cue me with words on where to place my focus and attention. I have no difficulty appreciating art, either, so it’s not some general pictorial problem.

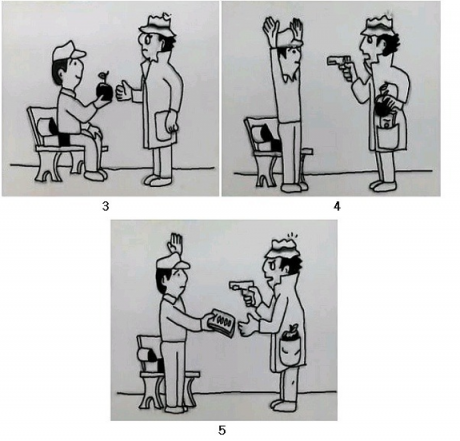

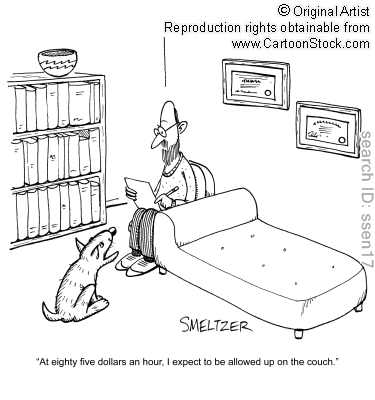

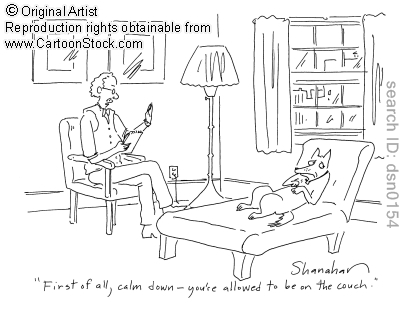

Years ago the New Yorker had one of its cartoon caption contests. I can’t find a picture of this one online, but it gave the entrant choices. The square consisted of the standard cartoon subject of couch and psychiatrist sitting behind it with notepad, and then a series of other characters (I recall a dog, a screwdriver, a woman, a man, and there were probably a few more as well) from which you could choose. You could place any one of the characters anywhere on the drawing, and then come up with a caption.

I had a sudden inspiration. I took the dog and placed it lying down on its back on the floor, facing away from the shrink, leaving the couch empty (the dog was drawn in such a way that you could easily do this, because each character was designed to recline). The dog was saying to the psychiatrist, “No, not the couch; there’s still too much guilt!”

I didn’t win, but I still like that cartoon.

And Google being the handy thing it is, a search revealed these. I still prefer mine, but they have a similar idea:

It took me quite a long time to figure out a quasi-reasonable ordering for the cartoon. (The result still wasn’t very satisfying…) My wife, also. And I (used to, anyway) score very high on standardized tests…

my best guess: 3,1,5,4,2

The gift of an apple is returned by a demand for money followed by the insult of the demand that the gift of the apple be taken back.

I think Jim is right. My problem with this cartoon is the first panel, #3. Supposedly, a man is offering a bum an apple from his lunch. But bums are usually more bum-like (this one merely has a rumpled hat), and usually the bum would be sitting and the other man would be walking past. And if the first panel is weird, it’s harder to reconstruct the rest.

One of my favorite cartoons (which don’t bother me, by the way) also involves a dog and a psychiatrist. The dog is lying on his back on the couch talking to the psychiatrist and the caption reads:

“Well, if I am being honest with myself, they’re not really accidents.”

}}} for example, those thought problems where you had to ferry some combination

Neo, I figure you’ll greatly appreciate Randall Munroe’s brilliant take on of one of these:

Logic Boat

“my best guess: 3,1,5,4,2” Don’t be modest, you kept your eye on the apple and found the solution. 🙂

A neighbor subscribes to the New Yorker and ‘gifts’ us her old copies. I rarely glance at any of the content except the cartoons. Some of them can make me laugh out loud. In particular I enjoy the last page.

}}} a screwdriver

LOL, the body/handle *below* the bit:

“Of COURSE I’m screwed up you nit! What am I supposed to do, stand on my head all the time?”

“No, not the couch; there’s still too much guilt!”

Hilarious, 10 times funnier than the ones that got published.

Wow, that cartoon sequence made my head spin. I stared it for several minutes, utterly confused.

I guess Jim’s sequence makes sense, but I want to put 1 later, as the robber is giving back the apple. He looks like he has a guilty or chastened expression on his face. But he doesn’t have the money in his pocket, so Jim is probably right.

When I was going through my parents’ papers, I found a report that I had scored 123 on an IQ test, at around age 12. But that was many fried brain cells ago. I shudder to think how I would score today.

As for cartoons as entertainment, I’ve always loved them. As a kid, the Looney Tunes ones were the best. I loved Road Runner. I don’t think I laughed that hard again until I discovered Monty Python years later.

I was also an avid reader of newspaper comic strips. My favorites as a kid were Peanuts, B.C., and Tumbleweeds. Later I followed Doonesbury and Bloom County. When I was in college, I had some books by B. Kliban. His cartoons were delightfully weird.

But by the time Calvin & Hobbes appeared, I was no longer reading newspapers on a regular basis. I would see that one now and then, but there were a lot of strips that I missed. My loss. Calvin & Hobbes is absolutely the gold standard for newspaper cartoons. They were artistically brilliant, intellectually challenging, and funny as all get out. If Bill Watterson had been an Olympic gymnast, he would have scored a perfect 10.

Well, now I feel better to know I’m not the only one who was stumped by that apple cartoon sequence.

I haven’t thought about Calvin and Hobbes in a long time. It is a classic cartoon series. Kids and adults enjoyed it equally. I’ll have to find some of the books and start reading the antics of Calvin with my older grandchildren.

I loved cartoons as a kid, especially the warner brothers madcap antics.

I will say, though, that as I’ve gotten older I tend to pick apart unreality more reflexively and shake my head at it more often. It’s not so much with cartoon physics, but with the entertainment industry’s outlook on ideals and such that has little connection to reality. That’s particularly true in entertainment that’s supposed to be realistic, which is why cartoons sometimes get a pass; I get irritated by too much of it, I think because I’ve seen too many people with a twisted perspective of what life should be after spending a lifetime exposed to Hollywood ethics. With Pixar and such, the visual medium is fine, but the “messages” grate more because they’re obviously delivered in such a way that the audience is supposed to find them genuine. That kind of artistic license we can do without.

While I watch PIXAR movies, I, too, find something disquieting about the animation.

THE “HYPOCRIT” THIEF:

3. Give me all you got

1. OK. Here’s all I got

5. This gun says you got more

4. Want your apple back?

5. I did a good thing!

Keep this test for aliens. Logic can’t solve it until knowledge of human situations is throw in. Kind of like Americans asking “Who is the pitcher for the Yankees?” in WWII. If you had trouble deciphering the pictures, you may have a touch of autism or sumpin.

PIXAR and CGI: We, the audience, are supposed to admire the artist rather than get drawn into the story. Are you more scared in the original 1950s “The Thing” (hokey but scary) or more scared of the sophisticated “The Thing” – where you (might) admire the craftsmanship? It’s part of the Hollywood focus-on-itself. One film where special effects artistry and scare-the-audience-by-igniting-their-inner-fears meet is the original “The Alien”.

I like animations to tell me about human life, not about the artistry of the artist who made them. “Persepolis” is good because it tells the story of a little Iranian girl whose grampa was a “communiss” and what happened to her world-view when she became an adult. I turned off “Wall-E,” “Ratatouli” (sp.), The Night Before Christmas”, “Toy Story,” and so many others – for lack of caring what impossible characters “do.” “Shreck” was different: it had story. That is not a criticism;it’s just a preference as to how to spend time.

The cartoon: work backwards. #4 has to be last, for he’s got the goods. #5 precedes it, for he’s getting them. #1 is in the middle. (or is it?) this leaves #2 and #3: Did he offer it first and then the robber walked away–i.e., #3 then #2? Or do we order them from his “sit” “stand” position? … he gave the apple away and then the robber gave it back? I then conclude: I DON’T CARE GRUMPPPHHH!, which is pretty much my feeling about PIXAR.

The contest: put the dog in the chair and the shrink on the couch and the dog says, “You don’t have to whisper.”

But the dog then whispered: I am not an animal.

I didn’t get it that the was money. I thought it was a brick and so the whole thing didn’t make any sense. Who would prefer a brick to an apple (unless a mason)?

nolanimrod: that’s exactly the kind of error I tend to make with cartoons (although in this case I actually did realize it was money).

But I get hung up not only on sometimes misinterpreting what an object in a drawing is, or not noticing it in the first place, but also—as in this one—overthinking, like thinking it was a LOT of money, a whole stack of bills. So it didn’t even occur to me that the guy would be handing over all that money for a mere apple!

Cartoons are just weird.

31542 – quick now that I know it is money.

Finally, only God can score intelligence.

5 4 1 3 2

25 seconds

Childhood IQ testing. Time, 2nd Grade. No, I don’t remember my being tested specifically but do remember a private meeting with a women, not from the grade school, who I spent time with in a small room near the Principal’s office who talked to me at length with the only question I recall these years later being about what I wanted to be in the future. This occurred circa 1949. As far as the testing making any impression on my schooling, it didn’t as I had already started school a year younger than my classmates and I was a behavioral problem to the teachers.

A few years ago Dad had stroke and entered a Nursing Home and soon died. Mother age 90 finally had to sell the house and dispose of accumulated detritis of living at same address for 70 odd years before entering assisted living facility.

My Sister found an envelope while cleaning out the house with my IQ test results from 1949 in a drawer and sent it to me. I had no idea it existed. On receiving the envelope a few mysteries were revealed. Two IQ tests were taken. First result was 145. Second was 165. Sister’s wry comment was: “Some spread, probably they mixed up the test results with someone else. Ha. Ha.”

Actually what happened: 1) First test was a Truncated IQ test with highest score 145; 2) Second test was from an one on one long form IQ test. The school had been told to identify any student with a top score and give that individual a non-truncated IQ test. The 165 IQ also explains my life so far.

Neither parent ever graduated from college. Mother was a house wife and had no intellectual life. Her parents were working class with the mother, my grand mother, being rather smart since she, having only a 6th grade education, worked on the side as a bookkeeper. My father had a high school education with some night school classes yet designed and oversaw the building of two specialized industrial plants. He then started his own industrial business running it successfully for over 25 years before selling it. It is still operating. His parents were immigrants but my grandfather always had a job because he was an artisan who worked in making decorative porcelain sinks and bathtubs something that took some smarts as well. My father’s mother had 11 children who made it to maturity so she was really, really busy as there only two girls.

I as a kid had no interest in school, rarely studied yet ended up in the top 20 of a class of 300, all boys, in an honor high school. I did well enough on the SATS to get a scholarship to college. My GREs got me into an Ivy and a Doctorate in a science. The GRE scores, take in 1963, correlate quite well with that 2nd grade 165 IQ as 800 verbal and 800 quantitative give 163 IQ. In addition my Navy Aviation IQ test which I took in the early 1960s, all visual, raw score was 116 correct out of 116. BTW, my field test GRE in a science score was 960 out of 970.

L’Homme Moyen

3-1-5-4-2. 4 confused me a bit because I just did not notice that the pocket contained the money and that the apple was being removed – apple location is above that shown in 1. That test, I think, gives the advantage to the sharp-sighted over the myopic. A few years ago a great cartoon on one of the psyche-blogs showed a man lying on a couch being analysed by a quite serious looking, button-down, horned rimmed glasses man and as he writes, over his shoulder we read his legal pad: “Nutty as a fruitcake”

You and your cartoon issues are a topic of discussion over at the Althouse blog, Neo.

M of Hollywood, I’d say you have Pixar/Dreamworks completely backwards. Shrek is the epitome of idiotic pop-infused gutter “humor” trying hard for an Aesop ending. Pixar is all *about* story. Sure, sometimes they don’t pull it off as well as they might, but they are far better than Dreamworks.

http://www.poe-news.com/forums/sp.php?pi=1001979235

Disclosure: I’m an animator by trade, versed in the ways of Pixar and Dreamworks, raised on a hearty diet of Disney with a dash of anime and Warner Brothers… but well steeped in the deeply moral Western deserts of Utah. There’s absolutely much that is detestable in Hollywood, but Pixar is head and shoulders above the norm.

…that said, Kung Fu Panda and How to Train Your Dragon were both better than Cars or Cars 2, so it’s all a bit muddled, really. *shrug*

Tesh: I’m not surprised I have them backwards. I rarely finish them – so what do I know. I happened to see Shrek in a studio theater, so I was probably influenced by the grand setting. So, no argument on Shrek.

A commenter over at Althouse wrote about this post: “I wonder if her ‘uncanny valley’ happens to be a lot wider than the average?”

I think that’s exactly correct for me. I have an uncanny valley the size of the Grand Canyon.

“I didn’t like watching the creature being flattened and then springing back up again.”

I agree. Once an animal is dead, I want it to STAY dead, you know? It’s why I never liked “Pet Sematary.”

I was always annoyed by bad drawing in cartoons — as for instance in the five-panel test here — and had trouble looking at the bad ones. As a child, I was working hard on learning to draw well representationally (I later majored in art and did some illustration) and it annoyed the heck out of me when cartoonists – who were getting PAID TO DRAW for godsakes, didn’t they realize how lucky they were? — contented themselves with bad work.

I made myself stare at this one long enough to decide that it’s 3-1-5-4-2 — bum asks for a handout, gets an apple, is offended by cheapness of handout, demands more, gets money, and gives back apple as a kind of trade. Dumb story, though, and it’s hard to puzzle out the lumpy half-baked shapes in the drawings, and what are those wiggly lines, half-erased in some of the panels, over the top of the bum’s hat?

Well-drawn cartoons, though, are a joy to look at. Calvin and Hobbes, for instance.