A trip back: the Iranian revolution (Part I)

[This is a repeat of a previous post. I thought to re-publish the series I wrote some time ago about the Iranian revolution. This is Part I.]

One of my favorite verses from The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam (the Fitzgerald translation of the Persian original) is this:

The Moving Finger writes; and, having writ,

Moves on: nor all your Piety nor Wit

Shall lure it back to cancel half a Line,

Nor all your Tears wash out a Word of it.

Ah, but if only we could go back, to wash out a few of the most terrible words! That’s the deep desire that propels most time travel fantasy: to undo some event that you know led to untold suffering.

The answer given by science fiction—and life—is that it just can’t be done. Even if it could, doing so might cause a cascade of other unforeseen effects. But the wish remains, especially for those happenings that seem to have been unmitigated tragedies for humankind.

One of those events was the triumphal return of Ayatollah Khomeini to Iran from his long exile in Iraq and his short sojourn in France (and Khayyam is an especially apt source to quote for the occasion—since modern day Iran is, of course, ancient Persia).

I was around when Khomeini made his return trip, one that propelled Iran’s own trip back in time to some horrific amalgam of the Dark Ages crossed with the tools of a modern totalitarian state. I noticed Khomeini’s arrival in Iran, although I had no idea of its significance. Neither did most.

He seemed and dark and brooding figure from some stern and gloomy ancient past. Or the sorcerer from Disney’s “Sorcerer’s Apprentice:”

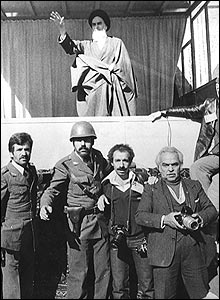

It was difficult to understand the veneration the Iranian people seemed to have for him. In this photo, taken on his return, he looks as though he’s already become a statue:

Here’s an article that chronicled the event. Reportedly, “up to” five million people lined the streets of the capital to witness it. The revolution he had helped orchestrate from Paris (how apropos!) was in motion; its Reign of Terror was about to begin.

Here’s an article that chronicled the event. Reportedly, “up to” five million people lined the streets of the capital to witness it. The revolution he had helped orchestrate from Paris (how apropos!) was in motion; its Reign of Terror was about to begin.

The Iranian revolution took almost everyone by surprise, including many of its participants. It was an amalgam of several of the strangest bedfellows in the world—a religious movement to impose a theocracy of strictest Islamic law, a group dedicated to Westernization and classical liberal human rights, and an active Marxist contingent.

All in all, a heady concoction that couldn’t fail to explode. The only question at the beginning was which faction would win out, because they certainly couldn’t all coexist. Khomeini was pretty sure he had an answer to that question. While in exile he had carefully played to the crowd that believed in human rights, but he made it crystal clear once he had consolidated his power that he had no intention whatsoever of following through on that score. Au contraire.

Khomeini addressed the assembled crowd at the Cemetery of Martyrs a few miles south of Tehran on February 1, 1979:

I will strike with my fists at the mouths of [the current Iranian] government. From now on it is I who will name the government.

Khomeni had learned his French lessons well: L’etat, c’est moi.

Shapour Bakhtiar, the newly-minted and ineffectual Prime Minister of Iran at the time–he had less than two weeks to go in that position—replied as follows:

Don’t worry about this kind of speech. That is Khomeini. He is free to speak but he is not free to act.

I almost wrote, “the ineffectual and clueless Bakhtiar.” But I’m glad I didn’t, because when I started to do some research on Bakhtiar himself, I found a man of rare courage and no small prescience, a tragic figure in history who made at least one fatal error.

In the summer of ’78 while hitchinking around town I got a ride with an Iraninan student who was going to some anti-Shah demonstration.

Fast-forward a year later. While working in Argentina, the central office sent an Iranian tcchnician down to install a computer part. He also taught math part-time nights at a university in the States. An Argentine woman asked him about having a theocracy in Iran. His reply was that if that was what the people chose, that was what they chose. Less than a week after he left to return to the US, the US embassy in Tehran got taken over. I never had a chance to ask his opinion of the subsequent events.

I doubt that he returned to Iran.