Welcome to the table, Ununbium

The Periodic Table, that is.

The new element, Ununbium, is number 112 on the list, and one of six highly unstable elements created in the same lab since 1981 (the last naturally occurring element is uranium, number 92).

To mark the occasion, I think it’s time for a reprise of one of my favorite essays, originally posted in September of 2006:

When I was in junior high school there was a huge poster of the Periodic Table of the Elements that hung in the science classroom in front of a little-used blackboard spanning the right side of the room, next to where I sat.

I’m not sure whether anybody in the junior high learned what the chart was about—we certainly didn’t. But it was a grim reminder of what awaited us in high school, when we’d be required to take Chemistry and Physics and Geometry and Trigonometry and a bunch of other subjects that sounded Hard, and sounded like An Awful Lot of Work.

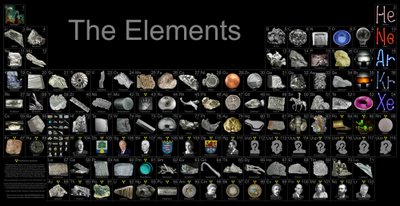

I wasn’t looking forward to the experience. In my more bored moments in class (and I had quite a few of them) I would glance at that chart on the wall and idly ponder its arcane mysteries. It looked like a more old-fashioned and slightly yellowing version of this:

That chart was the sort of thing that made me nearly sick to my stomach whenever I looked at it, something like slide rules and drawings of the innards of the internal combustion engine, and the long rows of monotonous monochromatic law books in my father’s office.

But then time passed—as time often does—and I found myself a junior in high school, sitting in chemistry class and finally (and reluctantly) about to penetrate the secrets of the Periodic Table. The teacher, a small, elderly (oh, he must have been at least fifty), enthusiastic, spry man, explained it to us.

I sat awestruck as I took in what he was saying. That chart may have looked boring, but it demonstrated something so absolutely astounding that I could hardly believe it was true. The world of the elements at the atomic level was spectacularly orderly, with such grandeur, power, and rightness that I could only think of one term for it, and that was “beautiful.”

I did very well in chemistry, and even thought of majoring in it in college, although in the end I stuck to psychology and anthropology. But I never forgot the lesson of the Periodic Table (actually, it taught many lessons, although some of them I did forget). But the one I remembered most was that appearances can be deceptive, and that what lies beneath a bland and stark exterior can be a world of magic.

And now (via Pajamas Media), I’ve finally discovered a Periodic Table worth its salt—or, rather, its sodium chloride. Take a look at this, a Periodic Table nearly as lovely as the elemental wonders it illustrates:

If you follow the link to the poster at its source, you can click on parts of it to enlarge them and see more of the detail. And then you might say with Keats:

When old age shall this generation waste,

Thou shalt remain, in midst of other woe

Than ours, a friend to man, to whom thou say’st,

‘Beauty is truth, truth beauty,””that is all

Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know.’

We ugly people resent being called liars, ma’am.

Neo, don’t know whether you have seen this, but it’s relevant, and a good piece of work to boot. For all I remember, I saw it here first…

Try a REAL Table of the Elements.

Real wood too.

http://theodoregray.com/PeriodicTable/

Seems like chocolate should be a fundamental element.

I remember feeling quite lied to when I found out those spherical and figure 8 valence shell orbital patterns were not really orbital patterns, like plantes around a star, but instead were pictures of mathematical probabilities where the elctrons might be found.

Of course, I should have known given that the simple spherical pattern was not a two dimensional ellipse- but somewhat falsely reported as a 3 dimensional sphere.

“planets” not “plantes” and “electron”, not “elctrons” I really need to start proof reading better. I scan, reading words often based on the first letters, and miss my many typos.

Here is an animated version of Tom Lehrer’s Elements Song. With a bow to Gilbert and Sullivan, of course.

Perhaps Mr. Lehrer will put out a new version of the song in accordance with what news has come to Harvard and other places.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zGM-wSKFBpo

Gringo:

Here’s an old post of mine about Tom Lehrer. It contains, among other things, a little anecdote about how the song “The Elements” once came in very handy for me.

I do teach AP Chem and Honors Chem, in addition to plain vanilla Chemistry.

The explanation of the Periodic Table is a triumph for quantum mechanics…so the level of sophistication depends on the course.

AP Chem gets the full treatment, ending with a derivation of the molecular orbitals of simple diatomic molecules…pre calculus is handy. Nothing to be unlearned later.

Honors gets the same basic treatment, stopping with hybrid orbitals and VSEPR. They are bright enough, but lack the math background to sweat the mathematical details.

Chemistry has to settle for a “Take my word for it” treatment. Gross similarities and trends in the rows and groups are the best I can expect, although they try to learn about electrons in bonding.

I do NOT make students memorize the names and symbols of elements. To do so is the sign of a lazy teacher whose knowledge ended a few decades ago. Students can always consult a periodic table when in doubt…that’s what she’s for.

As a chemist, I consider the Periodic Table to be probably the single most important breakthrough in the subject, because it systematized chemistry. The Periodic Table provided a conceptual framework to understand, think about, and even predict what superficially appeared to be wildly disparate observations.

I used to ask prospective students what discovery they would want to have made. Most said the structure of DNA, but for my money, it’d be the Periodic Table. Imagine how Mendeleev must have felt when he saw the pattern, or how Moseley (who, critically, shifted the ordering principle from atomic weight to atomic number) when he realized that he’d just explained why it worked! Magical.

Occam’s Beard: I’m with you on that. As I wrote in the essay, ever since I learned the way the Periodic Table worked I’ve thought it’s one of the most awesome things in the universe.

I actually think the best discovery is that of Pauli and his exclusion prinicple. Without that, the Periodic Table loses its structure. Deep down, that chart on the wall really means no two spin-1/2 particles can ever occupy the same state.

That said, I really do appreciate the intellecual tour-du-force that Mendeleev accomplished without the backing theory of Quantum Mechanics to help him along.

This discussion is reminding me of how much I have forgotten since my undergraduate days, especially considering the amount of chemistry I took.

Physicsguy, I’d turn it the other way around, myself, particularly since Mendeleev antedated Pauli by 60 years, and say that the Periodic Table helped to stimulate and guide the development of quantum mechanics by raising the question of why the table had the structure it did.

Clearly there was some principle underlying the table that needed to be discovered and understood.

The Aufbau principle explained why, e.g., there were only eight elements in the short periods.

So I’d say the quantum mechanics provided an explanation for why the Periodic Table has its structure.

Also, it’s important not to elevate theory over observation. If quantum mechanics should fall tomorrow (don’t laugh – Newtonian mechanics did!), any new theory will still have to explain the observed periodicity of elemental properties that Mendeleev systematized in his table.

Occam, the comment about elevating theory over observation is very important…. look what it’s got us into with respect to “global warming”.

Also, the comment that QM provides the ‘why’ of the Table is also right on… I’m just a bit awed with that ‘why’ on a daily basis 😉

However, I’m also eagerly awaiting the marriage of QM and Gen. Rel. which I think will have tremendous implications, OR a new theory which incorporates both in a completely new paradigm. That’s what makes science fun.