RIP Hugh Van Es

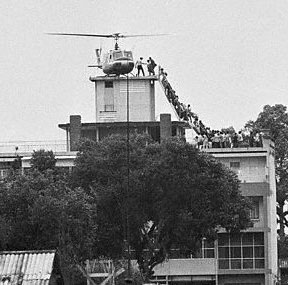

Hugh Van Es, the photographer who took the iconic “helicopters on the roof” photo of the fall of Saigon, has died at 67:

[Van Es’s] shot of the helicopter escape from a Saigon rooftop on April 29, 1975 became a stunning metaphor for the desperate U.S. withdrawal and its overall policy failure in Vietnam.

As North Vietnamese forces neared the city, upwards of 1,000 Vietnamese joined American military and civilians fleeing the country, mostly by helicopters from the U.S. Embassy roof.

A few blocks distant, others climbed a ladder on the roof of an apartment building that housed CIA officials and families, hoping to escape aboard a helicopter owned by Air America, the CIA-run airline.

From his vantage point on a balcony at the UPI bureau several blocks away, Van Es recorded the scene with a 300-mm lens—the longest one he had.

Van Es spent a great deal of time attempting (usually in vain) to correct the popular notion that his photo was of the US Embassy roof, where the bulk of the evacuations took place. Here’s his photo:

I’ve written several pieces about the fall of Vietnam and the meaning this and similar photos have taken on in the aftermath (see these posts). But today I’d like to reprise one of them, which describes the real story of the evacuations at the end of the war.

A view of that famous day in 1975, from eyewitness Col. Harry G. Summers, appears here, (see pages four through six). Col. Summers paints a vivid and detailed picture of the Herculean but ultimately unsuccessful efforts of the military to make sure everyone at the embassy was evacuated, as they had been promised.

One seldom-remembered fact is that the evacuation had been ongoing for several weeks, beginning with fixed-wing flights that had to be creatively managed because (in another seldom-remembered fact), the South Vietnamese government had barred its officials and its military personnel from leaving.

Even so, there was no way all those who wanted to go could be evacuated in time. But on that fateful day on the Embassy roof, Summers relates that all of those who had gathered there to be airlifted could have successfully escaped, and the majority there did. Of thousands who had already been helicoptered out from the Embassy alone on that single day and night, “only” 420 were left behind. Summers describes some of them:

America had not only fecklessly abandoned its erstwhile ally in its time of most desperate need but also had shamefully abandoned the last several hundred of those evacuees who had trusted America to the very end. Included were the local firemen who had refused earlier evacuated so as to be on hand if one of the evacuation helicopters crashed into the landing zone in the embassy courtyard; a German priest with a number of Vietnamese orphans; and members of the Republic of Korea (ROK) embassy, including several ROK Central Intelligence Agency officers who chose to remain to the end to allow civilians to be evacuated ahead of them and who would later be executed in cold blood by the North Vietnamese invaders.

After calming the panicky crowds by speaking in Vietnamese to them, clearing a landing area so that the choppers could do their work (it was impossible to evacuate the people by any other vehicle, since the streets of Saigon had become virtually impassible with the enormous crowds), why were the Marines forced to abandon some of their allies who had gathered at the Embassy?

The worst of it was that it was all unintentional, the result of a breakdown in communication between those on the ground running the embassy evacuation, those offshore with the fleet controlling the helicopters, and those in Honolulu and Washington who were making the final decisions. In short, it was the Vietnam War all over again.

As Summers tells it, there were only six planeloads left, and the Marines were determined to airlift them. But then the order came:

At 4:15 a.m. Colonel Madison informed Wolfgang Lehmann that only six lifts remained to complete the evacuation. Lehmann told him no more helicopters would be coming. But Colonel Madison would have none of it. We had given our word.

Madison and his men would be on the final lift after all the evacuees under our care had been flown to safety. Lehmann relented and said the helicopters would be provided. That message was later reaffirmed by Brunson McKinley, the ambassador’s personal assistant. But McKinley was lying. Even as he reassured us, he knew the lift had been canceled, and he soon fled, along with the ambassador and Lehmann, his DCM.

Apparently, the helicopter squadron commander back at the fleet had given the command to cease. But it was a misunderstanding; in Summers’s words, the commander had “believed they were dealing with a bottomless pit, and no one realized they were but six lifts from success.”

But it was too late now; the evacuation was over, and the images remain. And although it’s true that more of these people were successfully rescued that day than is commonly believed, it’s also true that they only represented a tiny fraction of those who wanted to leave but could not. The vast numbers of boat people who tried to follow later proved that, only too well.

My friends, Hai Tran and Xuan-An Tran were supposed to have been evacuated from the Embassy on that last day, along with their four children. He was a librarian for the USIS, she was a high-school science teacher, who had some connections to an experimental South Vietnamese nuclear power plant; both were considered to be in extreme danger from the North Vietnamese. They waited, and waited at home all during that last long day, for a phone call, or for someone to come and get them – no one ever did. Fortunately, Xuan-An’s brother was a Viet Coast-Guard commander, the captain of a 100-ft patrol boat. He had decided to make a run for it out to sea, at the last; he sent all of his crewmen into the city to fetch their families, and went to get his and Xuan-An’s mother. He was horrified to find them all still waiting, and urged them not to wait a moment longer. They came away with him, having to carry their youngest daughter, who was a toddler, and each of them with no more of their personal possessions than would fit into a small pack the size of a student’s book-bag.

Xuan-An told me there were a hundred people crammed onto that patrol launch, when they finally cast off and headed out to sea. There was a cargo ship, the Pioneer Contender, and an aircraft carrier, the Hancock, waiting just beyond the horizon.

The boy who lived with my family for a while, Kiet Huong Vo – he got away by helicopter, from the airport at Tan Son Nhut. He was a Vietnamese Air Force security policeman; he got carried away in a group of people rushing a helicopter. He was thrown up against the door, and on impulse, threw away his M16 and got on. He had not thought of escaping, really, but there was his chance and he took it.

He said that on the Hancock, as soon as they emptied people out of the helicopter, they pushed the helicopter overboard. There were so many people, and so many helicopter waiting to land and possibly almost out of gas and terribly overloaded, no place and no time to do anything else but shove them off the deck to make room for another to land.

I was antiwar, young and stupid, and believed the leftist propaganda until my early 30’s (1980s) when I had profound second thoughts. I cried when I heard that all the sleeping pills were sold out in Saigon when it fell; suicide was considered preferable to the oncoming Communist horde. Since then numerous books have documented the real history of the Vietnam War and its aftermath. I haven’t trusted the media since.

Neo,

I discovered this interesting clip the other day

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mcQoQDkhbYw

It sets the fall of Saigon to music.

I have appreciated your Viet Nam work Neo.

Mr. Time Machine

Here’s an appropriate link:

The Fall of Saigon

I would recommend the whole site; but especially President Ford’s letter where he says:

“We did the best that we could. History will judge whether we could have done better. One thing, however, is beyond question – the heroism of the marines who guarded the Embassy during its darkest hours, and those brave helicopter pilots who flew non-stop missions for 18 hours, dodging relentless sniper fire to land on an embassy roof illuminated by nothing more than a 35mm slide projector.”

Also, under misc photos, it shows the marines after they retreated to Manila reading the newspapers about what they have just done. They have just played a huge part in history! And they do, indeed, look so young.

I’m not at all sure if the above comment was suggesting my link was inappropriate. Perhaps I should have introduced it differently let’s try this:

“Summing this up as ‘The Saddest Day’ is appropriate, but perhaps misleading to the young or the still numb.”

link reposted:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mcQoQDkhbYw

It is good information!

My brother lost his life in the earlier days of the evacuation. The C5A transporting orphans out of country departed Ton Son Knut air base but accidently lost rear doors, thus de-compression and returned only to crash into a rice paddy and dike. It was a chaotic time with alot of urgency to leave. We did the best we could at the time. God bless those people we left behind.