Parents and homework wars, now—and then

This article at American Thinker describes growing protests by parents, who maintain their kids are overburdened and stressed out by too much homework. Author Charles J. Sykes takes issue, though, citing research to the contrary:

…a study by the Brookings Institution found that the great majority of students at all grade levels now spend less than an hour a day studying, or about a quarter of the time they spend text messaging things like “NMHJC” (Not Much Here, Just Chilling) to one another.

Sykes thinks many parents today are “obsessively involved, overprotective, indulgent moms and dads who have bubble-wrapped their children on the assumption that they are so frail and easily bruised that they must at all costs be protected against the symptoms of life, including, apparently, homework.”

He may have something there, although I also agree that certain homework assignments—usually the most infuriating ones, like dioramas, which I remember detesting as a child—are pointless and time-consuming “busywork” exercises.

The Sykes article brings back memories; I actually did have a fair amount of homework (yeah, I know, you’re weeping for me). And although this was in what were then called “gifted” and/or “honors” classes, I wasn’t in some private school, nor even a public school in a ritzy suburb. I attended public schools from kindergarten through high school in a relatively blue collar area of New York, and from about fifth grade on I recall having between three and four hours of take-home assignments a night.

My parents, like most parents of the day, were remarkably unconcerned about this fact. Of course, they were part of a culture in which schools were generally considered to know best, when it took some great and mammoth offense for teachers’ or principals’ judgments to be questioned. I don’t even remember my parents having the habit of asking me whether I’d been assigned homework on any particular night, or whether I’d finished it, either. I suppose they figured they’d know soon enough that there was something wrong if my grades began to slip. Otherwise, my homework was primarily my own work and my own business.

Except, that is, for a particular assignment I had in sixth grade, given by a teacher we’ll call Mrs. McGuire, who had a legendary and well-earned reputation for mental cruelty. The class was doing a topic on that perennial favorite (of teachers, anyway): inventors. Each of us would have to research a famous one, write a report about him (yeah, they were all men), and deliver it to the class.

Mrs. McGuire was not a believer in choice. She selected the inventor for each student, announcing the assignments as she read off our names. Some lucky stiffs got Edison or Samuel F.B. Morse, or even old Cyrus McCormick or Eli Whitney. This meant they could write their reports by looking up the information in that trusty Mother of All References (the only one any of us could easily obtain in those days), the home encyclopedia. If students were feeling really ambitious they could, of course, supplement the encyclopedia’s pedestrian offerings with a library book or two, and take home an A or a B without much further trouble.

But when she came to my assignment, Mrs. McGuire read out the arcane name “Nicolas Francois Appert.” Nowadays, in this glorious era of instantaneous Googling and Wikipedia (which I’ve just availed myself of), one can look him up fairly easily. Even so, the information is sparse (see also this); hardly the stuff of the fifteen-to-twenty-minute oral presentation we were all supposed to deliver back then.

But in sixth grade all I could find in the encyclopedia was one terse sentence, declaring Appert to be a Frenchman who’d invented an early method of preserving food, for which he’d been awarded a prize by Napoleon. A trip to the local library revealed not a word more. And so, in a state of upset, I told my mother, and enlisted her help.

My mother was convinced that Mrs. McGuire had given me this assignment in order to humiliate me, knowing that it would be impossible to fulfill. This didn’t activate my mother to complain to the school. She knew that several generations of parents had already done so about Mrs. McGuire’s many excesses—most of them far worse than this one, by the way—to no avail. But my mother was determined to show Mrs. McGuire a thing or two.

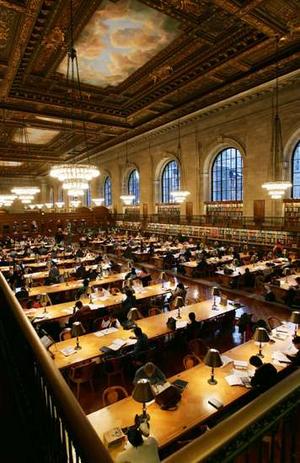

So that Saturday we went on an expedition to the 42nd St. branch of the NY Public Library, as impressive a building then as now, perhaps even more so in my eyes.

The journey was long, and I’d never been inside before. I recall that, when we entered the gargantuan research room (“a majestic 78 feet (23.8 m) wide by 297 feet [90.5 m] long, with 52 feet [15.8 m] high ceilings—lined with thousands of reference books on open shelves along the floor level and along the balcony; lit by massive windows and grand chandeliers; furnished with sturdy wood tables, comfortable chairs, and brass lamps”):

my mother was told children were not allowed. But when she explained to the astonished librarian what my homework assignment was, I was given special permission to stay (I believe even the librarian had a few choice words to say about Mrs. McGuire).

The enormous card catalog yielded only one book on the subject. One should have been enough, but unfortunately, this one was in French, and it was by, not about, Nicolas Appert. My guess is that it was the volume described by Wikipedia as having been entitled, “L’Art de conserver les substances animales et végétales (or The Art of Preserving Animal and Vegetable Substances for Many Years)”—an easy enough guess, since this seems to have been Appert’s only work.

We waited for the book to be delivered from the closed stacks, where its sleep had probably been undisturbed since the library’s opening in 1911. An ancient, slim volume, it turned out it held a mother lode (pun intended) of information, relatively speaking: its introduction (also in French) contained two or three pages describing Appert’s life, times, and mostly his invention.

Of course, we were not allowed to take the fragile (and decidedly rare) book home, but I sat at one of the tables and watched in awe as my mother read and translated the introduction, using whatever she remembered of her high school French, taking quick and dextrous notes (she knew shorthand, too) on a large yellow pad.

And that was it. I returned home with our prize, wrote a report, and delivered it. The kids in my class yawned (another inventor; who cares?), but Mrs. McGuire received my offering with a rather strange look on her face. I don’t know whether it was surprise, disappointment, or perhaps some combination of the two, but I didn’t much care.

What I experienced was mostly relief. My mother, however, owned up to a sense of triumph.

And the message of the whole strange episode? That you shouldn’t abandon a difficult but not impossible task, although sometimes help was needed to tackle it. That my mother could be a hero. That high school French and shorthand (neither of which I ever was to learn) might actually pay off, albeit in a somewhat strange set of circumstances. That the New York Public Library was a vast storehouse of knowledge, its mysterious underground bowels containing wondrous things.

And, I suppose, that research could be a sort of treasure hunt, an exciting adventure to uncover snippets of information heretofore unknown. Come to think of it, that latter lesson is probably responsible for some of my fascination with blogging.

And now, as I’ve completed the research (mercifully, all online) for this post, I discover that Appert’s story is still relatively hard to come by. As this source points out:

Nicholas Appert’s invention was tremendous; however, there is very little documentation on his personal and spiritual life. In this case, the invention appears to be more important than the inventor.

Tell me about it.

Great post!

This interior of New York Public Library – it looks great! Does it exist nowdays? If by some miracle I will visit New York in my life, I know the first place I would go.

Hmmm…

I’m not sure I agree. Certainly what’s expected of my children in their public schools seems to have declined in quality from what I remember from my Catholic school days, and I usually find myself nodding when you talk about uneducated, illiterate teachers – but my son’s experience in middle school was basically one of slowly drowning in hours of homework every night; far more than I remember having to do.

Now that he’s in high school, he seems to have finally mastered the knack of keeping ahead of the pile, but I’m waiting for my daughter to enter into the same middle school to see if she has a different experience, of if it was just my son’s poor habits that left him working at the kitchen table till 10 most nights.

Neo, your experience with “Mrs. McGuire” reminds me of my 8th grade Reading teacher. We were to write reports on any subject of our choosing, the subject to be approved by the teacher. I chose “Architecture,” as that was one of my early passions. I wrote a report on the history of architecture, from early times to the present; it was about 20 pages long, as I remember, with footnotes and bibliography (more work than either of my daughters were ever required to do in either high school or college). I contracted a very high fever during the time I was writing the report, and had to finish it while registering a temperature of 103. My mother took the report to school on the day it was due (I was still too sick to attend class), so the report wasn’t late.

When the reports were graded and returned to the students, the teacher would call each student up to the front of the class to receive their paper and grade. Grades were announced loudly, to the whole class. I received a “C” (the only grade lower than an “A” in any class that I had ever received up until that point) because the subject I had chosen was “too broad” (even though approved and vetted by the teacher beforehand). The teacher then proceeded to tear the report to pieces in front of me, saying “That’s because you’ll be tempted to use it in another class.”

She was not my favorite teacher.

This overprotecting attitude of teachers and parents to learning – does it have something to do with 20th place of US team at international school Olympiad on mathematics among 23 nations present? The first three places, traditionally, took Chinese, Indian and Russian teams. Of course, China and India combined comprise 2 billion strong population – sevenfold bigger than US, so much more human resources to draw from, but Russia has two times less population than US.

My kids had a lot of hours of homework. It started in elementary school, but it was not excessive.

My wife is a teacher and part of my work is done in the evenings, so the expectation that everybody would get to business after supper was in the air. I don’t think we ever, in all the years our kids were in school, had to suggest they get to it. Other households might have had a different experience solely because of the type of work the parents did.

The projects have a separate use besides busy work. They are problems to be solved. They reward initiative and planning. How and when the child does on the project could be a learning experience outside of the subject matter. As it certainly was for Neo.

I read all your posts, political and non-political, but this is my favorite so far. It reveals a lot about the development of your turn of mind, your patience and doggedness as a researcher and student of history coupled with your willingness to come to conclusions about what you’ve learned. That’s a rare combination, and one which has benefitted your readers — especially one like me, too lazy and scattered to do it for myself.

What a wonderful mother you have!

I loved dioramas, but I was a slacker kid who only put effort into art class. Making creative dioramas was the only way I could get decent grades in other subjects.

That’s a wonderful story – sometimes, homework is a learning experience for the parents too. Fortunately, my kids weren’t slackers, and we were often driving from place to place, or museum to museum, in an effort to complete a similar homework-inspired obstacle course.

The New York Public Library really is a grand place.

Thanks to the internet I had “canning” at the word “Napoleon.” Or maybe it was from “How Its Made” on cable TV.

I envy you the NYPL as a child. I had to make do with a one room library in Paradise, California.

One of those facts stored away in my packrat mind: the French Army, both revolutionary and Napoleonic, marched without a supply train, for the most part, and foraged on the land they happened to be marching through.

Wellington used this to advantage in Portugal with the Lines of Torres Verdes, one of the most formidable fortifications ever build. Not only did he fortify, he stripped the march route of the French army of any and all food, a scorched earth policy. The French settled down and proceeded to starve and had to retreat.

Voila!

That way this “Grand Army” was destroyed in Russia, too. Kutusov forced them to retreat by already foraged road. Only few made it to France.

Just a lovely article…..

It brought back memories of the paper I had to write in seventh grade. Mr. Clark, our geography teacher, announced to us the first day of Junior High School, that we would have ONE YEAR to do a report on a country we would draw out of a hat. The report would constitute a large part of our final grade, and would need to be formally constucted, with footnotes.

My senior thesis at Princeton did not prove to be as daunting a task.

I drew Thailand out of the hat. We were so far out in rural Pennsylvania, that there were no town libraries. The only sources of information were the Encylclopedia Britannica we owned at home, and the few encyclopedias in the school library. I wrote to the Embassy of Thailand and received a small packet of information.

All of my footnotes were the same; only the name and page number of the encyclopedia changed.

What did I learn? Well, Wally Cox, the comedian, wrote in his delightful biography (My Life as a Small Child), that he had learned that all the islands of the Pacific exported copra, and imported manufactured goods. That’s about what I learned about Thailand.

One classmate, who seldom spoke, but whom we knew to be Amish (remember this was RURAL Pennsylvania) wrote a two page paper in pencil on the back of some used sheets of paper……probably all he had.

Mr. Clark was a good teacher, and very well meaning, but I always thought that this assignment was some latent sadism.

I’ve got one child in high school and two in middle school at New York City private schools, so the homework question hits close to home. I’ve learned a few things in recent years.

In the Charles Sykes piece you linked to, he makes the standard point that our kids test poorly compared to kids from other countries in math amd science. If I understand things correctly, this turns out to be a bit of an apples and oranges comparison. In this country, just about everyone takes the standardized tests. In some of the countries that we are always being compared unfavorably to, only the smarter kids take those tests.

But that’s ultilmately a quibble. The more shocking fact I’ve learned is this — there is basically no evidence that high levels of homework (say, more than an hour a night, even in high school) — are actually beneficial. We all just assume it’s true, and we all think that since we had to do a few hours of homework a night when we were their age, they should have to do it too. But as I say, there doesn’t seem to be any empirical evidence that a heavy homework load leads to better achievement.

Finally, think of it from another angle. What is the optimal length of the workweek for a 10 year old or a 15 year old? Between classes and extracurricular activities, most kids spend about as much time at their “day job” as adults do. Then we ask them to spend a few more hours every night working. Is that healthy? Again, somewhat shockingly, there has been essentially no research done on this subject. But how would most adults feel if they were asked to work the total number of hours that these kids are expected to work during the course of the week? (Particularly when there is no reason to believe it improves their achievement.)

As a child I spent a lot of time reading for pleasure. If there is too much homework assigned, this will take away from time that could have been spent in reading for pleasure.

At the same time, I didn’t have the distractions from reading that children have today. My parents didn’t get a TV until I was 8- and that only because the son of a family friends, a physics major, spent his final semester with us after his parents retired to Arizona. He built us a TV in partial payment for room and board.

Your story about Mrs. Macguire reminds me of when I was pledging a high school fraternity. The fraternity president told me I was to write his English term paper for him to submit as his own. This guy had been particularly sadistic to me as pledge and I was really bummed about it. I told my mother about it and she got angry and came up with a great idea. We knew he was a poor student (C’s and D’s), so she decided to write the paper and make it better than any but the best student could have possibly done (she wrote for a living). I was thrilled because I didn’t have to write it. She was thrilled to stick it to the guy that had been making me miserable for the last several months. She wrote a 12 page paper on Jonathan Swift and Gulliver’s Travels, complete with footnotes and bibliography (this was before word processors) and used words like “matriculated”. When I gave it to the frat president, he was quite impressed and actually thanked me. The next week, he was glum because he received a A on form and an F on content. The F was because the teacher didn’t believe he actually wrote it. He couldn’t get mad at me because he thought I wrote it and just did a good job. I never told him the truth. My mother enjoyed that one much like I’m sure your mother enjoyed sticking it to Mrs. Macguire.

Until now I always thought that I just drew the short straw or the not to be found information for the term paper because it was me, you know , my bad luck or whatever. Now I now it was me but those authority figures were probably toying with me….thanks.

Sykes thinks many parents today are “obsessively involved, overprotective, indulgent moms and dads who have bubble-wrapped their children on the assumption that they are so frail and easily bruised that they must at all costs be protected against the symptoms of life, including, apparently, homework.”

I heartily agree with that. After judicial incarceration in a local liberal private school my daughter was left to the wilds of our local public high school. She is doing great.

Here is Cappy’s Lemma of Homework:

If you don’t do your homework, you flunk.

There. Pure and simple. No megasobs or psychobabble.

I have taught mathematics at the university level — to Freshmen.

IMHO, primary schools cover fat, far too much material. The increased “coverage” decreases depth. Depth of coverage is a function of insight, and insight requires time and work.

Most of the students I’ve taught know lots of facts. They’ve memorized them. They do not know how to reason. In fact, reasoning seemed odd to most of my students. In so many words they asked, “who’s the authority I’m supposed to parrot?”

The Trivium, grammar, logic, rhetoric, is no longer taught. When students study a subject like history or math, they are merely applying the Trivium to a specific topic.

My students knew lots of facts about lots of topics, but they didn’t know a damn thing about grammar or logic. Rhetoric was, to them, “whatever the professor said.”

Reduce “coverage,” and emphasize depth, the ability to reason about a subject.

Logic and the classical Greek history that went with it was deprioritized over new age beliefs such as Global Warming and Leftist ideology in universities and schools. What was once known as a Liberal Arts education no longer has much if anything to do with the classical liberal world.

Unless the teachers focus on war or good government vs bad government, history is just simply a bunch of facts on a timeline. Which is what it comes down to in the end and why so many don’t find history to be of interest or use.

Jeff and Ymarsakar are on to something, but I’m not sure they clearly identify the underlying causes. Public education over the past thirty plus years has been asked to provide an increasingly wider range of social service functions in addition to actual education. Teachers and counselors not only teach but have also been told they must deal with issues such as child protection, homelessness, hunger and so forth. This is not entirely new, but the ever-growing amount of time and attention these functions require take an increasing bite out of time for classic education. All of this during a time when the salaries and status of teachers has declined relative to its high water mark in the early Cold War era.

Then there is the “teach to test” bias that has developed, especially under No Child Left Behind. The amount of standardized testing going on and the ramifications (including threats of funding and even job losses) of having students in a given school do poorly on these tests has built in a bias toward cramming test oriented facts into the students’ heads as opposed to spending more time on grammar, logic and rhetoric. Built into this phenomenon is a bias toward “objective” fact learning as opposed to “subjective” assessments … like those required when a student does one of those big term papers.

My daughter wrote fewer pages during her entire high school career than I had to write for one single paper my senior year. That was a group project in International Relations. Our group of four was the smallest group and our paper was ‘only’ eighty plus pages. The largest group had I think seven members and it ran nearly 400 pages. We had half a year to work on it. Our group’s topic was the then on-going peace negotiations between players in the Viet Nam conflict. Virtually all the source materials for that topic were newspapers and various government documents. The larger group had the topic of U.S. relations with what was then called Red China. They had plenty of hefty tomes to use for references.

Everyone in the class took a couple of ‘field trips” to the New York Public Library to do research. Imagine the stir we made as a class of high school seniors (and a couple of very brainy juniors) boarding a morning commuter train. Despite the rule that kept us “children” from the inner sanctums at the NYPL, only one student got identified as being a banned high school kid rather than an allowed ‘adult’ college student.

As a college freshman I did a paper that was supposed to teach me to use the library system. The topic I choose (the life of the haiku poet Issa) turned out to be one like Neo’s; there were virtually no books on my subject. I went to five different libraries including the NYPL and turned up I think it was three sources. It was rejected. I dug out a paper I’d done in high school on Dylan Thomas, went to the campus library biography stacks and pulled out a handful of books on the Welsh bard in about ten minutes to further pad the bibliography. That paper got me an A.

Many of us, especially beyond a certain age, have had our “Mrs. McGuire”. I had an eighth grade teacher, a nun of the order of the Sisters of Saint Joseph of Carondolet, who was quite elderly and taughtus all, how ever many thirty plus young male and female louts there were, the entire repetoire of junior high school subjects. She made us memorize Joyce Kilmer and, because she was Irish, we all, Poles, Italians and others, had to memorize the counties of Ireland. Before it was normal, she started us on algebra–not exactly my favorite subject and especially when it was not required. Having her was a pain–remembering her is a joy because she was intelligent, hard, fair and had more intestinal fortitude than the toughest pugilist out there.

Thank you for your great post and a chance to see the reading room of the NYC main public library. I did also learn about Nicolas Francois Appert, the father of canning and, hopefully, a card to be found soon on Trivial Pursuits.

Homework.

For 5th and 6th grade I had the same abusive teacher (she, herself, put my name on her 6th grade list… she was fired ONLY after the children of other teachers were in her class… no one listens to parents) who asked one day if we thought students should be given homework.

I raised my hand (stupid or brave, I donno) and said that no, students shouldn’t be given homework.

Well into a tirade of deliberate humiliation about what a horrible thing this was to think, I realized that by “homework” she meant “assignment.” I was being berated in front of the class for an opinion I didn’t hold. What a pathetic creature I was to think that students should never have any assignments or work to do. Well, she could see how *I* would think so!

I don’t think that this crappy teacher was just part of learning to deal with life. Talking about her up to the age of 21 I’d start to cry. She was abusive and a parent would be arrested for it.

But my opinion on homework, which is the opinion my parents held as well, is that students spend 7 hours or more a day at school and if assignments can’t be finished at school *nomally* then something is very wrong. The amount of time that a student can usefully “attend” to instruction or information leaves half to 2/3rds of any class period available to do “homework.” There is no excuse for teachers to take away a young person’s limited free time because they can’t manage time for class-work.

Occasional assignments to be done at home or finishing up work that *could* have been finished in class is fine. But homework as a virtue?

Those who homeschool, even the ones who do so *diligently* find that the whole of “school”… ALL of it… can be accomplished in the number of hours daily that are often cited for “homework.”

So what’s going on? Send your kid to school all day long and then teach them at home in the evenings anyway? Why not just teach them at home in the evenings to start with?

What research (from memory, I don’t have the links and probably can’t find them) shows is that unstructured time is what promotes the ability to think.

Does “homework” help anyone? Does it help the bright student who “gets” all the concepts and is doing homework in the evenings? Or how about the student who struggles? All the bright student loses is time. The student who can’t understand or who is fighting with concepts *will not* understand or suddenly get the concept because he or she has been made to sit at the kitchen table for two hours or three or more. That student loses time and probably actually firms up those barriers to learning.

As for US math scores.

We don’t need all students to be math geniuses. We need the math geniuses to have the freedom to be math geniuses.

And the teacher who tore up the architecture report should have her own work vandalized, then she should be spanked in front of the class (humiliation for humiliation) and then she should be fired.

Thanks for a wonderful essay and also to all those who have made thought-provoking comments! What is the basic situation with respect to most public education? As the recent NEA report details, children are not being taught the joys of reading, and do not read. They think that “research” means “internet search”. They come to college quite ignorant of the history of their own nation and the culture out of which it arose. Their science and math scores are not globally competitive, so far as I recall. Many native speakers cannot write clear and coherent English.

From this point of view, I think the quantity of homework is the least of the problems–doing more at home of whatever it is that produces the grim results we are getting will hardly be helpful.

Homework, from my experience, would be better suited to finding out whether a student can solve certain mathematical problems. Such a person should also be reading certain chapters of the text. Then in class, students can either ask questions about how to do certain problems or they can acquire the actual solutions worked out on paper. This would ensure that if a person has a problem with one math problem, that the entire class time doesn’t need to be taken up addressing it. A student should be able to figure out for hmself why he can’t solve a problem, if the solution has already been worked out by the teacher. That can be done more efficiently at home than in class, where everyone is biding for the teacher’s attention.

A Socratic method of dialogue when studying history would also be of benefit. Certainly students can understand the text, dates, and events from their textbook at home, but it takes true conversation and asking those with greater experience than they, to truly figure out what all this stuff means. The more connections a person makes that they can relate to their own life, the easier they will remember such material.

Unless a person has naturally good memory with a natural genius for data retention, you will have folks that concentrate solely on memorization for memorization’s sake at the cost of true comprehension.

“from about fifth grade on I recall having between three and four hours of take-home assignments a night.”

So this would mean you did nothing but homework every night? If you got home from school at, say, 3:30, four hours of assignments would mean finishing at 7:30. Assume all breaks, including dinner, added up to an hour. You finish at 8:30. Not bad.

But add in a team sport or similar after daily school activity. Now you get home at 6:00. Finish homework at 10:00. Is that what you did?

What I have observed instead is a tendency for folks to overestimate the amount of assigned work they received, as they age. I certainly didn’t get four hours of work each night, back in the mid 1980s at my rural public school. Maybe we were slackers, but it didn’t seem to harm us.

Yes, I routinely went to bed very late during those years, and probably didn’t get nearly enough sleep. That’s the way I handled it. Some nights I commuted to Manhattan for ballet lessons as well, doing my homework on the subway (or trying to).

Your story was great and spot on as far as available information on the subject.

The library where you looked at Nicholas’ book, are you aware of how to obtain a copy of it?

Darren Appert

Darren Appert:

My guess is that the only way to see the copy is to go to either the NY Public Library, or perhaps the Library of Congress. But make sure the book is there, first.

Are you an Appert descendant?

I wonder how much affect running on little to no sleep has on the learning process. Considering the vast majority of us seem to do this while in college, it really makes me question how much we ever actually retain. :/