(Part 1)

(Part 2)

(Part 3)

(Interlude)

PREFACE

Part 4 has been a long time coming. The article itself is long, too–so long that I finally decided it would be best to divide it into segments, so readers might have a chance of swallowing it without getting a massive case of indigestion.

I’ll tell you what this post isn’t–it’s not a history of the war itself. It isn’t about those who fought in it, or the Vietnamese people who suffered through it. It’s a political psychological history, an attempt to describe how perceptions were formed in those who remained in this country, particularly those who were young liberals, or who became liberals as a result. So, please don’t castigate me for ignoring this or that aspect of the war; this is not meant to be comprehensive or definitive.

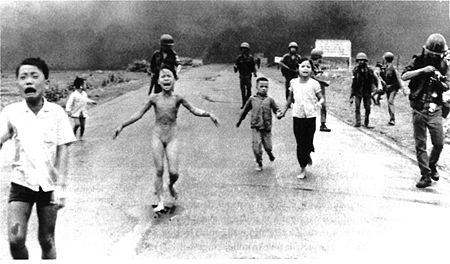

This first segment, Part 4A, deals with my own personal history during the Vietnam era. I start with it to set the scene, and because I think in many ways it is typical of liberals of the time, and can serve as a springboard for later, more general, discussion. Part 4B, which will probably come out tomorrow, is relatively short, and deals with some Vietnam-era photographs. If you think Part 4A is self-indulgent, or rambling, or pointless–after all, who cares about my history?–please bear with me; there’s method to my madness. The payoff (I hope!) will occur in Part 4C.

Part 4C, the third and final segment of Part 4, will probably be posted at the beginning of next week. It’s the part in which I attempt to bring it all together in terms of intrapersonal political change, the theme of this entire “Mind is a difficult thing to change” series. In Part 4C, I will be coming to some more general observations about how the Vietnam War formed (and, in some cases, transformed) political perceptions for many people of my generation, particularly liberals. In later posts (as yet to be written, but definitely on my mind), I will attempt to connect all of this to post-9/11 political change.

So, that’s my blueprint and my plan.

THE VIETNAM WAR–THE HOME FRONT

For those of you accustomed to the almost lightening-quick “major operations” phase of the Gulf, Afghan, and Iraq wars, it’s hard to get a sense of how agonizingly interminable the Vietnam war seemed to those of us who grew up during it. And the Vietnam war was long, even by WWI and WWII standards, although smaller in scope.

The first Green Beret advisors arrived in Vietnam in 1961, when I was still in junior high. The Gulf of Tonkin Resolution occurred in the summer of 1964, right before my senior year of high school, and the first US combat troops entered Vietnam shortly thereafter. In this manner, the war went from a distant background noise throughout my junior high and early high school years to a much more audible presence by my senior year of high school, and continued as a loud and discordant cacophony the entire time I was in college and for four years thereafter, with peace talks occurring in 1972, and the catastrophic US leavetaking in 1973. Saigon finally fell to the Communists in 1975. The toll in human life was high: the total number of US deaths there was over 58,000, with Vietnamese deaths in the war variously estimated as having been between one and two million.

The most serious escalation of the war coincided exactly with my college years, 1965-1969. I was younger than most of the other students; I had entered college shortly after my seventeenth birthday. We were all Cold War babies, having grown up with the constant threat of nuclear war but without the US actually having been involved in a major “hot” shooting war (except for the Korean conflict, which we were too young to really remember). So this was new to us.

I was very uneasy about the Vietnam war right from the start of the first troop commitments. At the beginning, the war upset me simply by the distressing fact that people were being killed; later on, I hated the war because it seemed unwinnable and thus an utter waste of human life.

Like most young people of the time, I took the war very personally. It’s probably hard to convey to later generations the powerful and all-pervasive nature of the draft, a sword of Damocles that hung over the heads of everyone. Even though I was a woman, and therefore couldn’t be drafted myself, every young man I knew was facing it, and so it affected me indirectly.

My boyfriend had flunked out of college (almost deliberately) in 1967, was drafted early in 1968, and six months later was sent to Vietnam and into heavy combat. Looking back, it seems to me that we were both painfully young. I was eighteen when we had begun to date, nineteen when he was drafted, twenty when he went to Vietnam, and barely twenty-one on his return. He was only one year older than I. I made sure I wrote to him every day while he was there. He was wounded and spent several weeks recuperating, but was sent back into the thick of the fighting. I was frantic with fear and pretty much alone with it; I didn’t personally know anyone else in college who had a loved one in a similar situation.

During the time he was there, and afterwards, I continued to hate the war (as did my boyfriend, by the way, although he felt it was his duty to serve). I hated the killing, was stricken by the nightly TV news featuring what seemed to be the same harrowing scenes played over and over: wailing Asian women clutching children, wounded soldiers on stretchers (I strained and squinted to see whether any of them looked like my boyfriend, because one of them might actually be my boyfriend), thick vegetation, burning huts. Over and over and over, to no seeming purpose, and with no end in sight. I could barely stand to watch, and sometimes I turned away, overwhelmed.

Throughout this time, both during the war and after, I was getting my news from several sources: network TV, Newsweek, Time, the Boston Globe, and the NY Times. I was under the impression that this represented a broad spectrum of news. These sources displayed a unanimity of opinion that I never questioned–after all, if so many highly respected media agreed, it must be because they were written by intelligent people who were seeking the truth, and telling it to us as best they could.

I remember Tet, Hue, Khe Sanh, all bunched together within a few short months in 1968, around the time my boyfriend was drafted. I remember those battles being portrayed as pointless scenes of carnage, signifying nothing. I remember the My Lai massacre, which also had occurred during the same time period, although we didn’t find out about it until a year later. It was deeply shocking to most of us; we had previously believed American soldiers incapable of such atrocities. We had been raised in the 50s on heroic WWII movies from the 40s, and had grown up with a press that had generally considered soldiers heroes, so this was a profoundly troubling revelation.

My attitude towards the war seemed to be quite typical, according to what I remember of my friends in college. We weren’t political junkies, for the most part, and hadn’t learned about the war in exhaustive detail. We read and/or watched the basic news and discussed the war, but in general terms–we felt we had the big picture correct, which was the most important thing, and we all agreed with each other, anyway. A few of my leftist friends (SDS was very active on my campus), spouted a more extreme version of events, in which they demonized the US–for example, I got into an argument with one friend who insisted that the goal of the US was to commit genocide in Vietnam–but the leftists seemed to me to be more interested in sloganeering and grandstanding than in actual facts or rational debate.

Of course, there were people who had different ideas about the war. But I personally knew none of these people, nor did I see their ideas being advocated in the media, for the most part. But there was the idea that the war originally had been both a good cause and a winnable one, although for political reasons the war had been mismanaged and fought in a half-hearted fashion. There was the idea that a liberal press had misrepresented the battles of 1968, including Tet, as defeats, when in fact they had been victories. There was the idea that, if we were to put more effort and money into it, the later policy of Vietnamization had a real chance of working and giving us the “peace with honor” we all desired, but the public had so turned against the war by that time that such money and effort would not be forthcoming.

But these voices seemed barely audible at the time. The only airing of some of these thoughts that I can recall was by John O’Neil during his June 1971 Dick Cavett show debate with John Kerry. O’Neill seemed sincere but naive and idealistic; Kerry had a world-weary air of having seen it all and known it all. But at least the debate provided food for thought and an airing of alternate views in a substantive manner, in a popular and readily-available forum. As such, it seemed unusual to me.

As time and the war had gone on, the tale told to us by the media wasn’t just about the war itself: it was about how the government had lied to the American people and deceived us, how it couldn’t be trusted. That message grew more focused during the early 70s, during the spring 1971 Congressional hearings on the war (the ones that featured John Kerry), and with the publication of the Pentagon Papers, which came out two months later. It was particularly convincing to hear disillusioned veterans such as Kerry speak out and demonstrate against the war–after all, they were the ones who been there and seen it firsthand. The Pentagon Papers revealed that the government had been deceptive about the war and the planning behind it. Then there was the invasion of Cambodia, perceived as an escalation of the war after Nixon had promised a reduction; and the killing of student protesters at Kent State by the National Guard, which made us feel as though war had been declared on us, too–on young people, on students. The message that the government could not be trusted was further reinforced by the Watergate scandal, commencing with the break-in in 1972 and ending later, after we had left Vietnam, in the ignominious 1974 resignation of Nixon.

If we couldn’t trust the government–well, then, who could we trust? Many decided to trust the whistleblowers: the press, our new heroes. After all, they had published the Pentagon Papers. They had shown us photos of what had happened at Kent State. They had brought the horror of My Lai to our attention. They had been instrumental in the exposure of the Watergate scandal, which had disgraced (and later was to bring down) a President most of us already disliked anyway.

WAR’S END

By the early 70s, virtually everyone I knew had become convinced that the war had been a tragedy and that the lies were so endemic we had no way of learning the truth from the government. I attended the 1969 march on Washington and a few smaller rallies. I believed that what the US had tried to do–prevent the Communists from taking over the whole country–had been a worthwhile goal, but an impossible one.

It seemed that, in our efforts to prevent that takeover, we had caused great damage. I wasn’t even sure that the Vietnamese people had ever wanted us there in the first place, or that they supported the South Vietnamese government; there seemed to be so many North Vietnamese, and they just would not give up. What about that domino theory, anyway, the original justification for the war? It was just a theory, after all–was it even true, did it actually apply here? If the war kept going on this way, indefinitely, Vietnam itself would be destroyed (if it hadn’t already been), and more and more Americans would die, too, all in a losing cause.

Therefore I rejoiced as we pulled troops out, and was happy about the peace talks. I watched some of the footage of the fall of Saigon, and was heartsick, but I believed nothing could have prevented this–it had been inevitable, and better sooner than later, after more death and destruction. Finally, I turned away from those pictures, just as I’d turned away, at times, from footage of the war itself–too painful, too hopeless, too sad, too powerless to help.

These Vietnam memories and judgments remained encapsulated within me for the next thirty or so years, untouched and unexamined, a painful and unhealed wound. I saw no reason to re-examine them, and nothing to make me doubt them. They lay dormant but retained their potency, needing only the right conditions to germinate in surprising ways much later, post-9/11.

UPDATE: Part 4B has been posted.